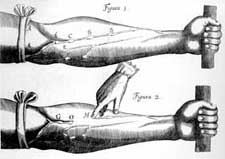

In the 1600s the study of life changed forever. After relying on the authority of ancient writers like Aristotle and Galen for centuries, European naturalists began to look at life for themselves. Anatomists discovered new organs in the human body, and also discovered that familiar organs didn’t work the way Aristotle and Galen said they did. The English physician William Harvey (above left), for example, discovered in the early 1600s that blood was pumped from the heart through the body in a closed loop. Meanwhile, Harvey and others were examining animals and plants and making equally astonishing discoveries. The English inventor, Robert Hooke, for example, looked through a microscope at a previously unimaginable complexity hidden in tiny animals as humble as a flea.

Envisioning organisms as machines

This new generation of naturalists envisioned life as machines. Like human-made machines, an animal had many different parts—muscles, eyes, bones, organs, and so on—that all played vital functions to help keep the animal alive. Naturalists found that they could apply the same scientific methods in physics that they used to invent machines, to life itself.

Natural theology and God’s design

Some clergymen worried that this mechanistic approach of life smacked of atheism. But many of the naturalists themselves believed that they actually were on a religious mission. In fact, a number of them were both naturalists and theologians. They believed that God had created the entire world in such a way that his plan could be understood in part by rational creatures. By studying the intricate structures of a hand or a feather, a naturalist could appreciate God’s benevolent design.

Natural theology, as it became known, dominated English thinking for nearly two centuries. In the early 1800s, it was best known to Englishmen through the writings of Reverend William Paley (left). Natural theology was important scientifically because it guided researchers to the fundamental question of how life works. Even today, when scientists discover a new kind of organ or protein, they try to figure out its function. But it would be Charles Darwin, who actually occupied Paley’s rooms at Cambridge University and was an admirer of Paley’s work, who would take science beyond natural theology and move those questions from the religious sphere to the scientific.