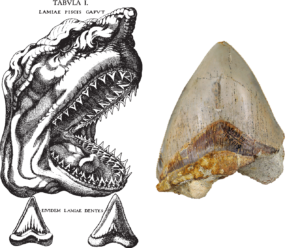

If one day in history had to be picked as the birth of paleontology, it might be the day in 1666 when two fishermen caught a giant shark off the coast of Livorno in Italy. The local duke ordered that this curiosity be sent to Niels Stensen (better known as Steno), a Danish anatomist working at the time in Florence. As Steno dissected the shark, he was struck by how much the shark teeth resembled “tongue stones,” triangular pieces of rock that had been known since ancient times.

If one day in history had to be picked as the birth of paleontology, it might be the day in 1666 when two fishermen caught a giant shark off the coast of Livorno in Italy. The local duke ordered that this curiosity be sent to Niels Stensen (better known as Steno), a Danish anatomist working at the time in Florence. As Steno dissected the shark, he was struck by how much the shark teeth resembled “tongue stones,” triangular pieces of rock that had been known since ancient times.

Today, most people would instantly wonder whether the tongue stones were giant petrified shark teeth, but in 1666 such a presumption was a tremendous leap. Few could imagine how living matter could be turned to stone, and beyond that, encased in solid rock—especially if the rock were well above sea level and contained remnants of a marine organism. Fossils were instead thought to have fallen from the sky, or to be “sports of nature”—peculiar geometrical shapes impressed on the rocks themselves.

From living tissue to stone

Steno made the leap and declared that the tongue stones indeed came from the mouths of once-living sharks. He showed how precisely similar the stones and the teeth were. But he still had to account for how they could have turned to stone and become lodged in rock. Naturalists of Steno’s day were becoming convinced that matter was composed of different combinations of tiny “corpuscles”—what today we would call molecules. Steno argued that the corpuscles in the teeth were replaced bit by bit, by corpuscles of minerals. In this gradual process, the teeth didn’t lose their overall shape as they turned from tissue to stone.

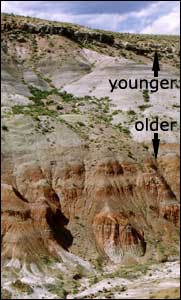

Steno’s Law of Superposition

But how could fossils end up deep inside rocks? Steno studied the cliffs and hills of Italy to find the answer. He proposed that all rocks and minerals were originally fluid. Floating on the surface of the planet long ago, they gradually settled out of the ocean and created horizontal layers, with new layers forming on top of older ones. Molten rock sometimes intruded into the layers, reaching the top and spreading out into a new layer of its own. As the rocks formed, they could trap animal remains, converting them into fossils and preserving them deep within their layers. Those horizontal layers represent a time sequence with the oldest layers on the bottom and the youngest on top, unless later processes disturbed this arrangement. This ordering is now referred to as Steno’s Law of Superposition, his most famous contribution to geology.

Steno was not the only naturalist of his day to propose that fossils belonged to living creatures. Leonardo da Vinci and Robert Hooke, for example, also took up the same view. But Steno pushed the idea much further. He argued for the first time that fossils were snapshots of life at different moments in Earth’s history and that rock layers formed slowly over time. It was these two facts that served as the pillars of paleontology and geology in future centuries. And fossils ultimately became some of the key evidence for how life evolved on Earth over the past four billion years.