The mechanisms of evolution — like natural selection and genetic drift — work with the random variation generated by mutation.

Factors in the environment are thought to influence the rate of mutation but are not generally thought to influence the direction of mutation. For example, exposure to harmful chemicals may increase the mutation rate, but will not cause more mutations that make the organism resistant to those chemicals. In this respect, mutations are random — whether a particular mutation happens or not is generally unrelated to how useful that mutation would be.

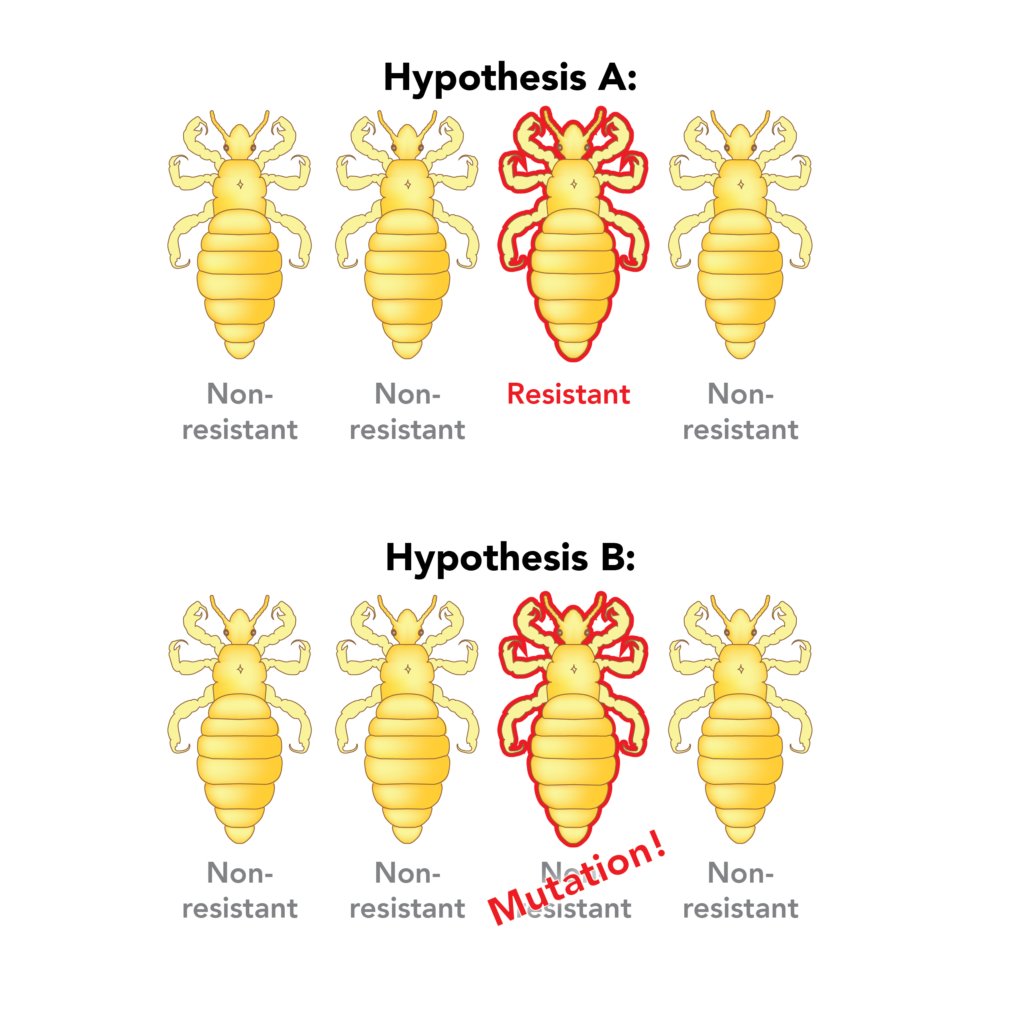

In the U.S., where people use shampoos with particular chemicals in order to kill lice, we have a lot of lice that are resistant to the chemicals in those shampoos. There are two possible explanations for this:

Scientists generally think that the first explanation is the right one and that directed mutations, the second possible explanation, is not correct.

Researchers have performed many experiments in this area. Though results can be interpreted in several ways, none unambiguously support directed mutation. Nevertheless, scientists are still doing research that provides evidence relevant to this issue.

In addition, experiments have made it clear that many mutations are in fact “random,” and did not occur because the organism was placed in a situation where the mutation would be useful. For example, if you expose bacteria to an antibiotic, you will likely observe an increased prevalence of antibiotic resistance. In 1952, Esther and Joshua Lederberg determined that many of these mutations for antibiotic resistance existed in the population even before the population was exposed to the antibiotic — and that exposure to the antibiotic did not cause those new resistant mutants to appear.

Read more about how mutations factored into the history of evolutionary thought

Learn more about mutation in context:

Find lessons, activities, videos, and articles that focus on mutation.