Geographic isolation

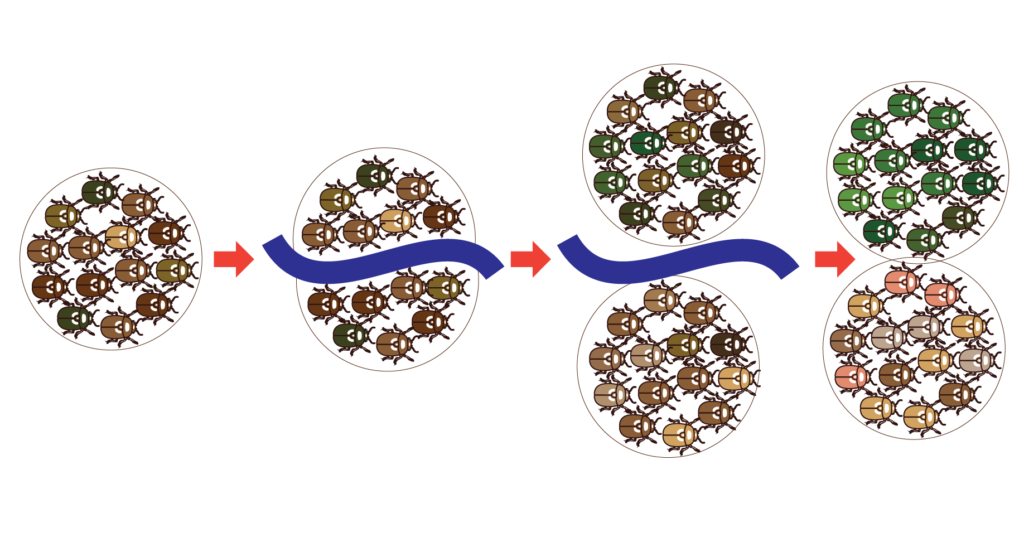

In the fruit fly example, some fruit fly larvae were washed up on an island, and speciation started because populations were prevented from interbreeding by geographic isolation. Scientists think that geographic isolation is a common way for the process of speciation to begin: rivers change course, mountains rise, continents drift, organisms migrate, and what was once a continuous population is divided into two or more smaller populations.

It doesn’t even need to be a physical barrier like a river that separates two or more groups of organisms — it might just be unfavorable habitat between the two populations that keeps them from mating with one another.

Reduction of gene flow

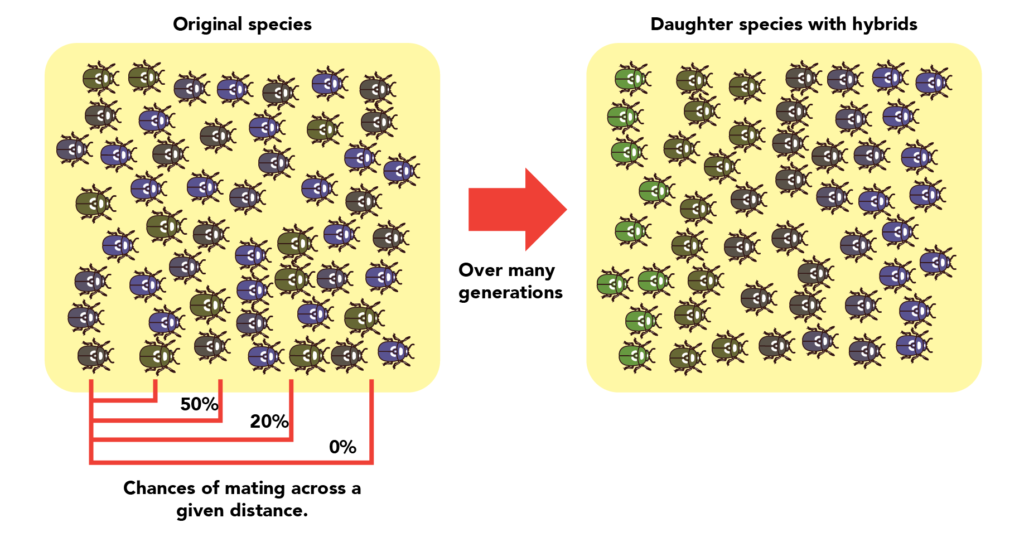

However, speciation might also happen in a population with no specific extrinsic barrier to gene flow. Imagine a situation in which a population extends over a broad geographic range, and mating throughout the population is not random. Individuals in the far west would have zero chance of mating with individuals in the far eastern end of the range. So we have reduced gene flow, but not total isolation. This may or may not be sufficient to cause speciation. Speciation would probably also require different selective pressures at opposite ends of the range, which would alter gene frequencies in groups at different ends of the range so much that they would not be able to mate if they were reunited.

Even in the absence of a geographic barrier, reduced gene flow across a species’ range can encourage speciation.

Read about how speciation factored into the history of evolutionary thought. Or explore different modes of speciation, including:

Learn more about speciation:

- A closer look at a classic ring species: The work of Tom Devitt, a research profile.

- Sex, speciation, and fishy physics, a news brief with discussion questions.

Teach your students about speciation:

- Anolis lizards, a classroom activity for grades 9-12.

Find additional lessons, activities, videos, and articles that focus on speciation.