Despite being such an ambitious mission, the spacecraft performed almost flawlessly and returned the collector back to Earth in 2006 with both cometary and interstellar dust grains lodged in the aerogel, as well as some particles that hit the surrounding foil. After landing in the Utah desert near the U.S. Army’s Dugway Proving Ground, the Stardust collector was transferred to NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, TX, and remains there still. However, carefully extracted bits of aerogel were sent to clean rooms at UC Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory and elsewhere, as one of the most challenging parts of the project was yet to begin.

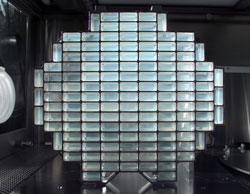

The collector is about one tenth of a square meter in size, or about the size of a small bicycle wheel. That might not seem very large, but the interstellar dust particles hidden within the collector are absolutely minuscule — typically about a micron across — and so finding them isn’t easy. “We collected about 300 micrograms of cometary material in total,” says Westphal, “but only one millionth that amount of interstellar dust. Initially we assumed we would use optical microscopes to find the dust particles. Aerogel is transparent, so you can see tracks left by the particles as they slammed into the collector. The problem is that these tracks are so tiny you would have to search about one million microscope fields of view to find them.”