2024 Stories

We live in the age of humans, but it’s not the Anthropocene … yet

While you’ve probably heard of the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods by way of their most charismatic animals, the dinosaurs, other units of geologic time are less well known. The Siderian Period, for example, rarely makes headlines because it is, by definition, old news – 2.5-billion-year-old news. However, discussions of geologic time recently sprang up in news feeds when geologists considered shaking things up and declaring the end of the Holocene Epoch, which we’ve been living in since the last Ice Age ended more than 11,000 years ago. The idea was to cap the Holocene by sectioning off a new unit of time called the Anthropocene – the age of humans. Here we’ll dig into the geologic time scale to see why it matters and what the idea of the Anthropocene Epoch is all about.

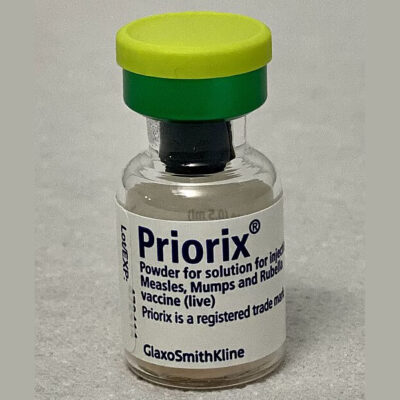

Read more »Measles: New outbreaks, old virus

In recent weeks, measles cases have popped up across the U.S in Ohio, Florida, Washington, Michigan, Indiana, Minnesota, and beyond. This highly contagious virus often leads to hospitalization and occasionally to serious complications and death, especially in children under five. While the vaccine is safe and effective, declining vaccination rates have left pockets of people vulnerable. Measles might sound like ancient history compared to COVID-19, mpox, Zika, and other outbreaks that have made headlines in recent years – but how long has measles really been around? Evolutionary biology has the answer.

Read more »Why species stay the same

The word evolution is nearly synonymous with change. One species diversifies into many. A disaster triggers a mass extinction among marine life. A microbe becomes resistant to our drugs. Each of these changes, large or small, is a classic example of evolution in action. But what about lack of change? Most of the species we observe around us today look about the same as they did in our grandparents’ time. And the fossil record includes many species that seem hardly to have changed at all for millions of years. How does this conspicuous stability square with evolutionary theory? New research supports one explanation.

Read more »2023 Stories

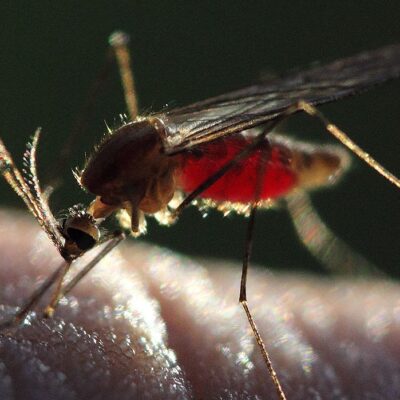

Menacing mosquitoes: Nature or nurture?

Last month, a California resident was infected with dengue fever after a bite from a local mosquito. This case made the news because it was the first, but it may not be last. Dengue and another mosquito-transmitted disease, malaria, are on the rise around the world. Several factors are behind this trend. Climate change allows mosquitoes to live in broader geographic regions. A city-dwelling mosquito species has been transported across continents and established itself in dense urban areas. And, importantly, mosquitoes have changed.

Read more »Are we boosting the evolutionary potential of SARS-CoV-2?

It’s baaack! COVID-19 is surging again, but this time, its symptoms are milder. That’s probably because vaccines and previous infections have led to some degree of immunity. And even when symptoms aren’t mild, we now have treatments to help those most at risk of severe disease. However new evidence suggests that one of those treatments, the medication molnupiravir, causes mutations in the virus and that these mutant viruses can be passed from person to person. Should we be worried?

Read more »Familiar sparks for ancient extinctions

Around 10,000 years ago, two-thirds of Earth’s large mammals blipped out of existence. Mammoths, mastodons, sabertoothed cats, and many other species from all over the world went extinct. Despite investigating many possible causes, biologists have yet to find a smoking gun revealing the culprit behind the disappearances. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that we are missing something. Extinction can be, well … complicated. Perhaps we haven’t been able to identify a single main trigger for the extinctions because several causes acted together. A new study takes this possibility seriously and untangles the interacting factors behind large mammal extinctions in Southern California at the end of the last Ice Age.

Read more »Meteorite impact no picnic for sharks either

Around 66 million years ago, a massive meteorite struck Earth, triggering a series of ecological disasters that wiped out T. rex along with all the other non-bird dinosaurs. For most of us, that’s old news – and might be as much as we know about this dramatic time. But scientists, of course, dig much deeper into the past, investigating exactly how mass extinctions played out and how they affected different groups of organisms. Now, new research explores this same extinction event from the view of another ancient and famously toothy group: sharks, skates, and rays.

Read more »How did dinos get so big…and so little?

Dinosaurs come in all sizes. The lumbering Argentinosaurus probably reached 115 feet, the winged Microraptor less than 4 feet. And today, the sole surviving lineage of dinosaurs – modern birds – includes both miniscule hummingbirds and leggy ostriches. (Learn more about why birds are actually a type of dinosaur here.) Scientists have long been interested in how non-bird dinosaurs, which include the largest land-dwelling animals that ever lived, came to have such different body sizes. The answer, of course, is through evolution, but what evolutionary changes were involved? New research helps answer that question.

Read more »Nature or nurture? In tiger snake evolution it’s complicated…

Seeing differences in the biological world often leads to questions about nature and nurture. Did I outperform my sibling in basketball because I inherited my mom’s quick reaction time (nature) or because I practiced more (nurture)? Is this golden delicious apple really old (nurture) or are they just a mealy apple type (nature)? Is our dog well behaved because she’s part golden retriever (nature) or because of all that puppy training (nurture)? Often the answers to such questions are not either/or. New research on venomous tiger snakes highlights just how intertwined nature and nurture can be – and how evolution has a hand in both!

Read more »