2019 Stories

Reconstructing locomotion with fossils, footprints, and… robots?

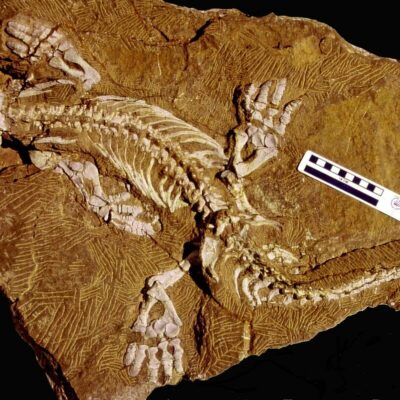

Right around 350 million years ago, long before the evolution of dinosaurs or mammals, animals that looked a lot like oversized amphibians started colonizing dry land. Over the past few decades, scientists have discovered many more fossils of these critters and learned about their anatomy and diversity. But we’re still not quite sure how our earliest four-legged cousins walked — did they slink around on their bellies, like salamanders, or did they hold their legs underneath their bodies, more like crocodiles? And what does this mean for the evolution of terrestrial locomotion? A recent study brings us a big step closer to the answer.

Read more »New twists on ancient DNA

DNA looks like a delicate molecule: a narrow twisted ladder, perhaps two inches long, but just two nanometers wide. What would it take to destroy such a thin chain of atoms? More than one might think! Researchers have calculated that under common conditions, it would take more than 500 years for half of the chemical bonds in a molecule of DNA in bone to disintegrate — and under ideal conditions, it could survive much longer. This surprising sturdiness underlies the field of ancient DNA, which has so far managed to reconstruct genetic sequences from samples up to 700,000 years old (in the case of an ancient horse frozen in permafrost). Of course, such information provides a fascinatingly detailed glimpse of evolutionary history, revealing for example that humans and Neanderthals interbred, as well as which human gene versions came to us from our Neanderthal ancestors. This past month, two new studies highlighted how we can squeeze even more genetic information out of ancient remains.

Read more »‘Puppy-dog eyes’ produced by evolution

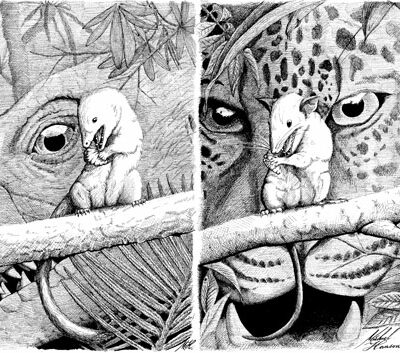

If you are a dog owner, you likely think of your dog as a true friend — a creature you can relate to and who relates to you. This connection doesn’t need words. Perhaps your dog looks up at you and makes those big puppy-dog eyes, and you know his meaning: time for a treat! New research suggests this phenomenon is neither an accident nor your imagination. Domestic dogs’ ability to communicate with us via facial expression is instead the result of tens of thousands of years of dogs’ evolution alongside humans.

Read more »How did early mammals chew?

Unless you have a toothache, it’s easy to take chewing for granted. We crunch through foods like nuts and fruit without thinking much about the anatomical equipment that makes it happen. But we know from fossils that our earliest mammalian ancestors didn’t have a single lower jaw bone like we do today; instead, they had left and right jaw bones that could move independently. How did early mammals chew? And how has mammalian chewing evolved over the past 250 million years? Recent research reveals clues.

Read more »Another crystal clear snapshot of life in the Cambrian seas

When most of us think of fossils, we probably picture bones — dinosaur bones pieced together into a skeleton, leaving observers’ imaginations to fill in the blanks of the organs, muscles, and skin that once hung on that frame. The drawers of paleontology museums are also crammed full of teeth, shells, and other hard bits of living things that don’t easily rot away, leaving them available for fossilization. But every so often, when circumstances on ancient Earth were just right, far more than hard parts were preserved. Last month, scientists announced the discovery of a fossil bed in China laid down in one of those unusual circumstances. It provides a fascinatingly detailed glimpse of life in the ocean 518 million years ago, long before any animal had ever heaved its hard bones onto dry land.

Read more »Whales lose teeth, gain baleen

The 380,000-pound blue whale is not only the largest animal on Earth, but the largest to have ever lived on Earth. A blue whale would even have tipped the scale on a titanosaur, the heaviest dinosaur, which weighed less than half of what a blue whale does. But these whales do not leverage their size to become the top predator of the seas. In fact, they are toothless and feed relatively low on the so-called food chain, feasting on tiny crustaceans called krill, which measure just a centimeter or two long. This is only possible because of a specialized filter-feeding structure called baleen, which hangs in sheets from the top of the whale’s mouth. Blue whales gulp up a mouthful of krill-rich water and then push it back out through their baleen, sieving out all the krill in the process. Without baleen, blue whales (and their behemoth brethren, all members of the group Mysticeti) could not achieve their enormous sizes. How did the evolutionary innovation of baleen arise? New research sheds light on this fascinating transition.

Read more »One route to lighter skin, two different continents

Skin color is one of the most obvious physical characteristics that distinguishes one person’s appearance from another’s. However, the trait itself, its genetic basis, and its evolutionary history are complex. Human skin color ranges, not just between dark and light on a single axis, but over a whole landscape of shades and hues. Even within a single region, like Africa, skin color varies widely among different populations. Fittingly, many different genes are known to affect a person’s skin tone. Last month, scientists announced that a gene version usually thought of as a “European” gene, for playing a major role in explaining the light skin of Europeans, was also favored among KhoeSan, populations native to South Africa that have relatively light skin in comparison to many other Africans. How and why did these geographically and physically distinct populations wind up with the same snippet of DNA?

Read more »