Where's the evolution?

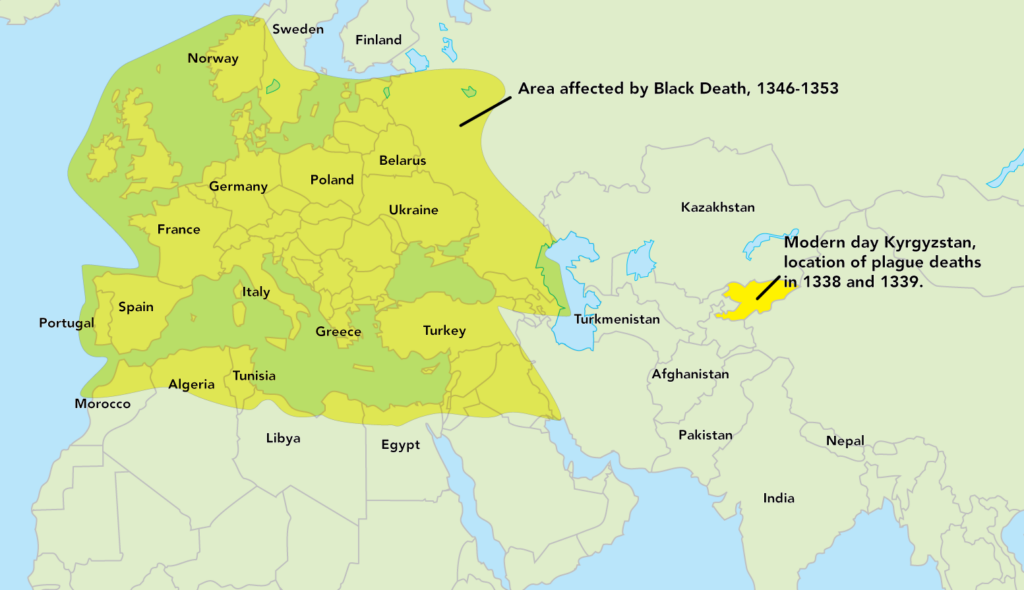

The cemeteries near Lake Issyk-Kul in modern-day Kyrgyzstan were first excavated in the late 1800s. Researchers had long suspected that bubonic plague was responsible for many of the dead – and the new research further buttressed this idea. An unusually large number of burials dated to 1338 and 1339, just before the Black Death in Europe, and some of the tombstone inscriptions specify the cause of death to be a “pestilence.” To get more direct evidence, scientists searched for ancient DNA in the excavated human remains and found what they were looking for: genetic sequences from Y. pestis, clear evidence of bubonic plague.

Timing-wise, it seemed plausible that the plague epidemic rattling ancient Kyrgyzstan in 1338 and 1339 had simply spread westward, sparking the Black Death in Europe, Western Asia, and North Africa in 1346, but the evidence was circumstantial. A more definitive answer would require evolutionary reasoning.

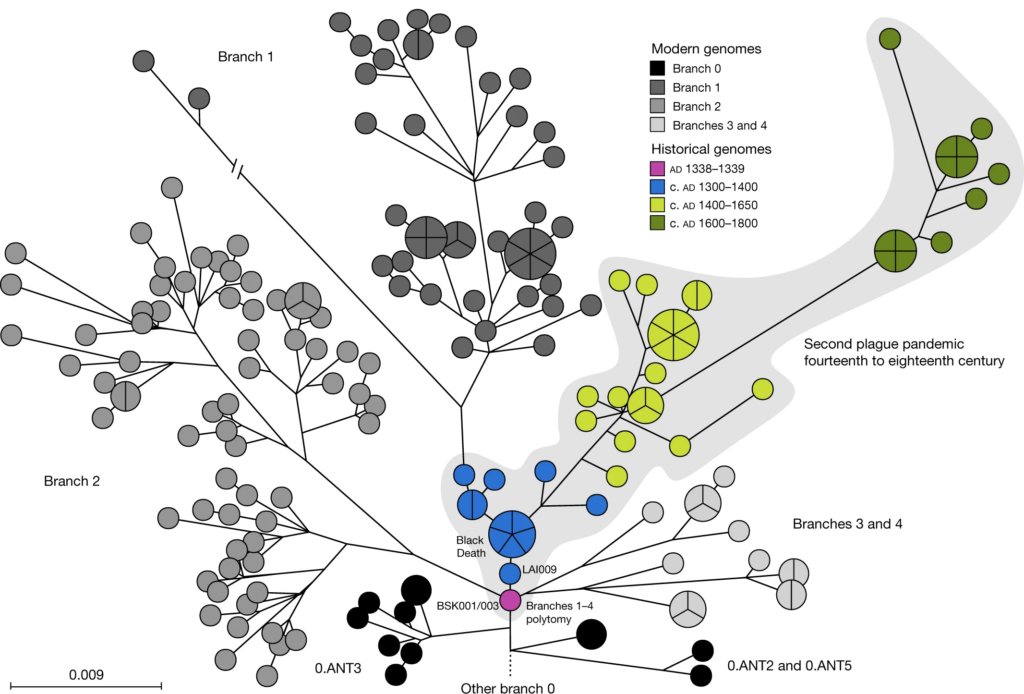

The researchers gathered Y. pestis DNA sequences from other places and times – including other ancient DNA sequences that were clearly part of the Black Death and sequences from modern strains of Y. pestis. They used these to build an evolutionary tree, or a phylogeny, showing how all the different strains are related to one another. The tree supported previous research, which found that there are several different modern strains (branches 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 on the tree below), with the Black Death sequences (in blue below) all clustered on a single branch. The Black Death sequences, as well as those from later outbreaks in Europe (in green below), are all very closely related and are, in fact, each other’s closest relatives. This suggests that the Black Death and those later outbreaks of bubonic plague were not caused by multiple invasions of slightly different strains of Y. pestis from different areas, but a single event where a lineage of sparked a pandemic and then stuck around, continuing to diversify.

Remarkably, the evolutionary analysis placed the Y. pestis DNA sequence from the Kyrgyzstan graves (in pink above) at a central node of the tree, in between branches 2, 3, 4, and the Black Death sequences. This means the Y. pestis DNA from the Kyrgyzstan graves exactly matched the sequence that we we would expect the evolutionary ancestor of the Black Death strain (as well as the ancestor of branches 2, 3, and 4) to have. This is strong evidence that the lineage of Y. pestis that caused the Black Death passed through the communities around Lake Issyk-Kul before reaching Europe, in a sort of ‘prequel’ plague.

To try to figure out where the plague strain might have been before infecting people near Lake Issyk-Kul, the researchers searched for Y. pestis DNA sequences that branched off the tree before the Kyrgyzstan plague sequence arose. These represent other descendants of the ancient Y. pestis lineage (the ‘pre-prequel’ plague) that gave rise to the Kyrgyzstan plague. They are shown as the black 0.ANT strains on the tree above. These sequences – the modern descendants of the pre-prequel Y. pestis lineage – mainly came from wild animals very near the Kyrgyzstan site. This suggests that the Kyrgyzstan plague may have arisen locally, spilling over from local populations of marmots into the human population, and from there moving west.

Since the Kyrgyzstan site is also close to ancient trade routes between Eastern Asia and Europe, the researchers further hypothesize that trade may have played a role in spreading this strain of Y. pestis from Kyrgyzstan to Europe and North Africa, where it sparked a pandemic causing at least 10 times more deaths than COVID-19 has so far. Evolutionary theory can help us understand the circumstances that led to past pandemics, with the hope that we can use this knowledge to better prevent them in the future.

Primary literature:

- Spyrou, M. A., Musralina, L., Gnecchi Ruscone, G. A., Kocher, A., Borbone, P., Khartanovich, V. I., … and Krause, J. (2022). The source of the Black Death in fourteenth-century central Eurasia. Nature. 606: 718-724 Read it »

News articles:

- An article and podcast about the new research from the CBC

- Another review of the research from CNN

- A podcast covering the discovery from Nature

Understanding Evolution resources:

- List three lines of evidence that suggest that Kyrgyzstan graves include individuals who died of bubonic plague.

- Compare the dates of the plague deaths in Kyrgyzstan to the dates of the Black Death. What hypothesis about the origin of the Black Death are these dates consistent with?

- On the phylogeny in the article above, the dark green dots ( Y. pestis genomes from 1600-1800) branch off from the light green dots (Y. pestis genomes from 1400-1650), which branch off from the blue dots (Y. pestis genomes from the Black Death, 1300-1400). In your own words, describe what this pattern of branching means about the relationships and evolutionary history of these Y. pestis lineages.

- Examine the phylogeny in the article above and describe how it supports the hypothesis that the Y. pestis lineage that caused the Black Death first passed through Kyrgyzstan.

- What evolutionary evidence suggests that the plague that the caused the deaths in Kyrgyzstan came from local wild animals?

- Teach about evolutionary trees: This lab for grades 9-12 has two parts. In the first, students build phylogenetic trees themed around the evidence of evolution, including fossils, biogeography, and similarities in DNA. In the second, students explore an interactive tree of life and trace the shared ancestry of numerous species.

- Teach about uncovering the evolutionary origins of diseases: This news brief for high school and college describes research offering insight into when (and how) HIV got its start. It includes several updates showing how scientists have built on this research over the course of a decade.

- Spyrou, M. A., Musralina, L., Gnecchi Ruscone, G. A., Kocher, A., Borbone, P., Khartanovich, V. I., … and Krause, J. (2022). The source of the Black Death in fourteenth-century central Eurasia. Nature. 606: 718-724