In recent weeks, measles cases have popped up across the U.S in Ohio, Florida, Washington, Michigan, Indiana, Minnesota, and beyond. This highly contagious virus often leads to hospitalization and occasionally to serious complications and death, especially in children under five. While the vaccine is safe and effective, declining vaccination rates have left pockets of people vulnerable. Measles might sound like ancient history compared to COVID-19, mpox, Zika, and other outbreaks that have made headlines in recent years – but how long has measles really been around? Evolutionary biology has the answer.

In recent weeks, measles cases have popped up across the U.S in Ohio, Florida, Washington, Michigan, Indiana, Minnesota, and beyond. This highly contagious virus often leads to hospitalization and occasionally to serious complications and death, especially in children under five. While the vaccine is safe and effective, declining vaccination rates have left pockets of people vulnerable. Measles might sound like ancient history compared to COVID-19, mpox, Zika, and other outbreaks that have made headlines in recent years – but how long has measles really been around? Evolutionary biology has the answer.

Where's the evolution?

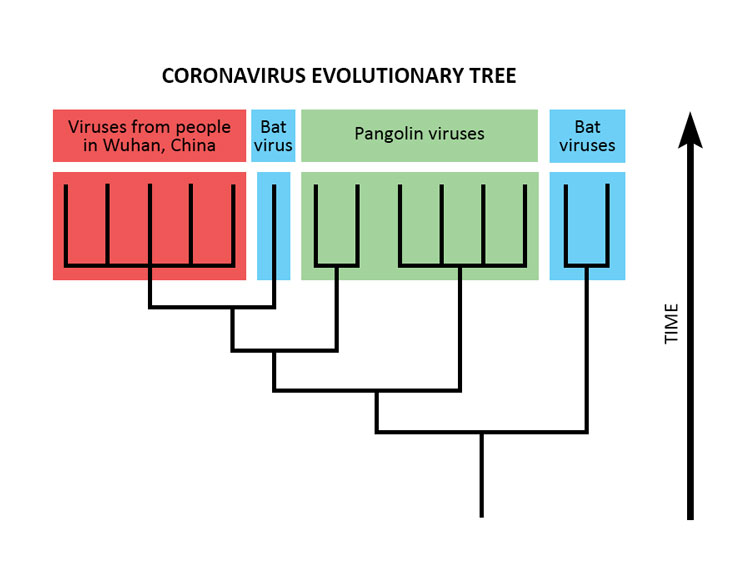

We can uncover the origins of viral diseases by reconstructing their evolutionary trees, or phylogenies. Biologists collect genetic information from many different strains of the disease-causing virus and compare these to the DNA or RNA sequences of other viruses using computer programs. This analysis determines which viruses are likely to be most closely related to one another and how long ago their evolutionary paths likely diverged. For example, early studies of the virus that causes COVID-19 revealed that it may have evolved from an ancestral virus that infected bats.

A similar analysis showed that HIV has evolved from viruses that infect non-human primates many times. The tree also revealed that the HIV strain responsible for most infections (subtype M) probably made the leap into a human host around 1908 and circulated undetected for decades.

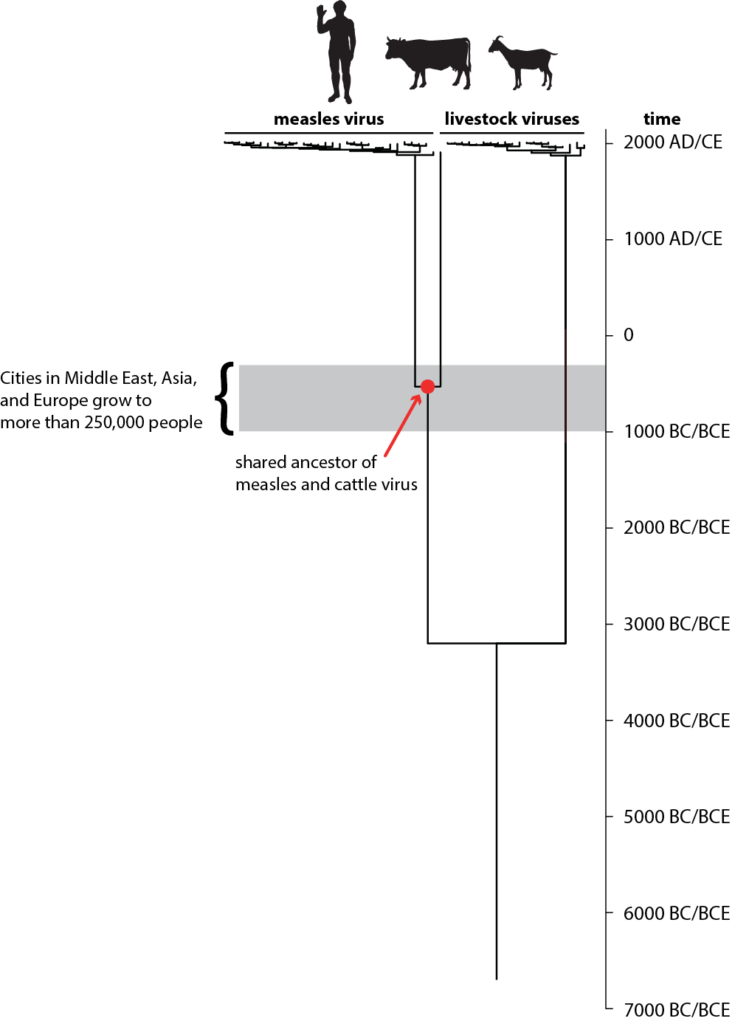

A 2020 study investigated the evolutionary history of measles. To get as close to the ancestral measles strain as possible, the researchers sought out old medical collections and were able to get genetic sequences from a lung tissue sample of a 2-year-old girl who had died from measles in 1912. They combined this information with sequences from a 1960 measles strain and many more modern viruses to reconstruct the evolutionary tree showing how all the viruses are related.

Measles belongs to a family of viruses that mostly infect livestock. The very closest relative of modern measles is rinderpest virus, a devastating cattle disease that was finally eradicated in 2011 thanks to vaccination. The research narrowed in on the timeframe in which measles arose. Between 2000 and 3000 years ago (around the time the Buddha lived in South Asia and shortly before Socrates was born), a cattle virus split into two descendent lineages: one evolved into modern rinderpest, the other into measles.

This timeframe for the origin of the measles lineage stood out to the biologists because it is close to the time that the first major cities with more 250,000 inhabitants arose in the ancient world. This occurred in North Africa, India, China, Europe, and the Near East around the same time. That’s notable because the measles virus depends on dense human populations to survive. Viruses persist by producing offspring that infect susceptible individuals. If, at any time, the virus runs out of potential victims (e.g., after a broad epidemic or a successful vaccination campaign), it will go extinct, blipping out of existence. Measles produces strong immunity, so once someone has had measles, they can’t be reinfected. Hence, in small populations, measles is likely to run out of potential victims before new ones are born, snuffing the virus out entirely unless it is reintroduced from another community. In fact, scientists have estimated that measles can only persist in groups of 250,000-500,000 people.

The aligned timing of the growth of cities and the origin of the measles virus, suggests that the development of large human settlements allowed measles to stick around after making the jump from cattle to humans. The ancestors of rinderpest virus may have found their way into humans before this, but because these populations were small, the virus died out. Only once cities existed was a mutant cattle virus able to gain a foothold in the new host, evolving into the devastating human disease that still kills more than 100,000 people each year, most of them young children.

Vaccination could, of course, prevent these deaths. In fact, vaccination could do even more. Scientists and medical professionals agree that, with sufficient support and effort put towards vaccination programs, measles could be eradicated – wiped off the face of the Earth forever. Humans have lived, and died, with measles for a few thousand years. Perhaps, that’s long enough.

Primary literature:

- Düx, A., Lequime, S., Patrono, L. V., Vrancken, B., Boral, S., Gogarten, J. F., … Calvignac-Spencer, S. (2020). Measles virus and rinderpest virus divergence dated to the rise of large cities. Science. 368: 1367-1370. Read it »

News articles:

- An article on the recent rise of measles in the U.S. from PBS Newshour

- A summary of the research on measles’ origin from New Scientist

Understanding Evolution resources:

- Why did the scientists behind the research described above need to collect genetic sequences from measles and related viruses?

- The hypothetical evolutionary tree to the right shows the relationships among four viruses.

- Circle and label the parts of the diagram that represent modern viruses.

- Circle and label the part of the diagram that represents the most recent shared ancestor of virus C and D.

- Virus A infects rodents, viruses B and C infect bats, and virus D infects humans. What hypothesis does this evidence suggest about the origin of virus D and its host prior to infecting humans? Explain your reasoning.

- Mark and label the part of the diagram that represents the viral lineage that first started infecting humans according to the hypothesis.

- Study the evolutionary tree of measles and livestock viruses in the article above. Describe two key pieces of information about the origin of measles that you can glean from this tree.

- In your own words, describe the evidence suggesting that the rise of large cities might have been important in the origin of measles.

- Imagine that scientists are studying a new infectious disease. They study the genomes of virus samples taken from different patients and build an evolutionary tree. The tree shows that the samples from humans are all closely related to viruses from mice. They are more distantly related to viruses found in possums. However, the human samples do not form a cluster, or clade. Instead they are spread out over the tree, and some are most closely related to other human viruses, but others are more closely related to mouse viruses than they are to other human samples.

- Based on this evidence, what do you think the source of the new disease is? Explain your reasoning.

- Based on this evidence, do you think the virus jumped to humans from another species once or many times? Explain your reasoning.

- Teach about evolutionary trees: This lab for grades 9-12 has two main parts. In the first, students build phylogenetic trees themed around the evidence of evolution, including fossils, biogeography, and similarities in DNA. In the second, students explore an interactive tree of life and trace the shared ancestry of numerous species.

- Teach about emerging infectious disease: In this case study for undergraduates, students explore changes in SIV (Simian Immunodeficiency Virus, thought to be a precursor to HIV) in different chimpanzee populations and how researchers use this information to test hypotheses about the origins of HIV.

- Teach about evolutionary trees and medicine: This research profile for high school and undergraduates follows scientist Satish Pillai as he studies the evolution of HIV within infected individuals. His research uses the tools of phylogenetics to investigate vaccine development and the possibility of curing the disease.

- Cochi, S. L., and Schluter, W. W. (2020). What it will take to achieve a world without measles. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 222: 1073-1075.

- Düx, A., Lequime, S., Patrono, L. V., Vrancken, B., Boral, S., Gogarten, J. F., … Calvignac-Spencer, S. (2020). Measles virus and rinderpest virus divergence dated to the rise of large cities. 368: 1367-1370.

- Plantier, J., M. Leoz, J.E. Dickerson, F. De Oliveira, F. Cordonnier, V. Lemée, … and F. Simon. 2009. A new human immunodeficiency virus derived from gorillas. Nature Medicine 15:871-872.

- World Health Organization (August 9, 2023). Retrieved February 23, 2024 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles

- Zhou, P., Yang, X., Wang, X., Hu, B., Zhang, L., Zhang, W., ... Shi, Z. (2020). Discovery of a novel coronavirus associated with the recent pneumonia outbreak in humans and its potential bat origin. bioRxiv preprint. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.

01.22.914952.