While you’ve probably heard of the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods by way of their most charismatic animals, the dinosaurs, other units of geologic time are less well known. The Siderian Period, for example, rarely makes headlines because it is, by definition, old news – 2.5-billion-year-old news. However, discussions of geologic time recently sprang up in news feeds when geologists considered shaking things up and declaring the end of the Holocene Epoch, which we’ve been living in since the last Ice Age ended more than 11,000 years ago. The idea was to cap the Holocene by sectioning off a new unit of time called the Anthropocene – the age of humans. Here we’ll dig into the geologic time scale to see why it matters and what the idea of the Anthropocene Epoch is all about.

Where's the evolution?

The geologic time scale connects Earth’s rock record with events in its history, providing a framework for scientists to understand the timing of volcanic eruptions, asteroid bombardments, mass extinctions, adaptive radiations, and much more over the last 4.5 billion years. When scientists first began to develop the geologic time scale, it was purely relative – that is, we could say that the rock layers (i.e., strata) containing trilobite fossils were deposited before the rock layers with dinosaur fossils, but not how much more. As our dating techniques have advanced, we’ve been able to put more and more precise numbers on these strata and, hence, on the events they represent and correspond to. This is called absolute dating.

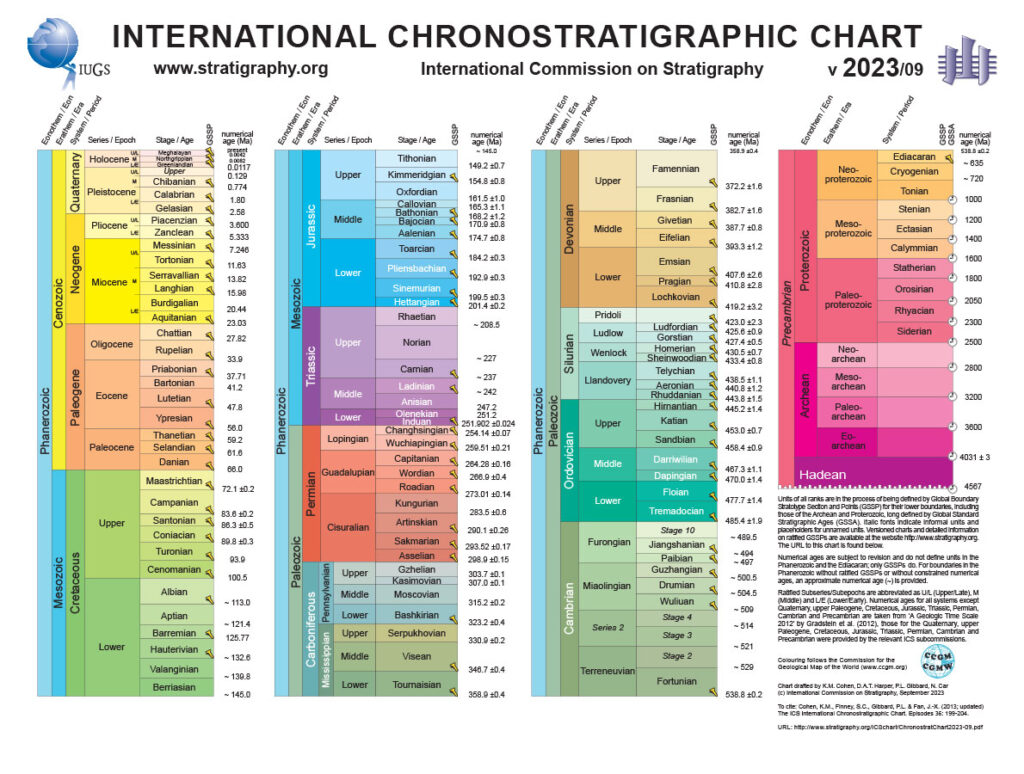

The geologic time scale divides Earth history into four eons: the Phanerozoic, Proterozoic, Archean, and Hadean. Eons are divided into eras, eras into periods, periods into epochs, and epochs into ages. An organization of scientists, the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), determines what properties of the rocks will be used to define these divisions. For example, some strata might be defined based on the sort of fossils they contain and others on physical characteristics of the rock or even on its magnetic orientation.

For the last 15 years, ICS geologists have been researching the best way to define the Anthropocene in the rock record, and correspondingly when, exactly, it began. What best demarcates the time period when humans dominated and reshaped the planet? Should the start of the Anthropocene be signaled by the appearance in sediments of tiny bits of plastic, by pesticides, by pollution from burning fossils fuels, or by something else? The team ultimately decided the epoch-in-the-making should start when a spike of plutonium (from hydrogen-bomb testing, a clear marker of modern humanity’s impact on the world) appeared in the sediments of Crawford Lake in Canada in 1952.

The ICS committee tasked with evaluating such changes ended up rejecting the proposal, but certainly not because humans are “leaving no trace” in the rock record. In fact, one point of disagreement was that the proposal did not recognize the drastic effects humans had on the planet well before 1950. After all, we humans have powered our industry with polluting fossil fuels for more than a hundred years, we’ve been cutting down forests and broadly altering the landscape for thousands of years, and we’ve probably been causing significant extinction events for tens of thousands of years. Does the year 1952 really capture the scope of what we mean by the Anthropocene? Perhaps not. Other voices in the geological community argue that the Anthropocene should be considered an ‘event,’ an occurrence that may transform Earth systems in many ways, but which is not designated as a unit of time.

The committee’s rejection of the proposal may yet be appealed, but whether or not the Anthropocene becomes official, scientists broadly agree that human activity is reshaping the planet and its systems in dramatic and often devastating ways. The age of humans is certainly epic, just not epoch … at least not yet.

Primary literature:

- McCarthy, F. M. G., Patterson, R. T., Head, M. J., Riddick, N. L., Cumming, B. F., Hamilton, P. B., … and McAndrews, J. H. (2023). The varved succession of Crawford Lake, Milton, Ontario, Canada, as a candidate Global boundary Stratotype Section and Point for the Anthropocene series. The Anthropocene Review. 10: 146-176. Read it »

- Walker, M. J. C., Bauer, A. M., Edgeworth, M., Ellis, E. C., Finney, S. C., Gibbard, P. L., and Maslin, M. (2023). The Anthropocene is best understood as an ongoing, intensifying, diachronous event. Boreas. 53:1-3. Read it »

News articles:

- A summary from the New York Times

- An editorial on the topic from Nature

- A personal perspective from one of the scientists involved, from UMBC Magazine

Understanding Evolution resources:

- In your own words, summarize the proposal about the Anthropocene that the ICS recently considered.

- Review the topics of relative and absolute dating. Describe the difference between the two in your own words.

- Choose an event or organism from Earth history that interests you (e.g., the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs, or trilobites). Do some research online to determine when it happened or lived.

- Describe the event/organism.

- Explain the timing of the event/organism in absolute terms (number of years ago) and give the corresponding time units of the geologic time scale (e.g., during the Cambrian Period).

- Review this article from New York Times and this one from UMBC Magazine. In a paragraph explain whether you think that the Anthropocene should be designated a new epoch and give your reasons. If you think it should, be sure to include how you think it should be defined. If you think it should not be, explain why not.

- Teach about geologic time: In this web-based module, primary, middle, and high school students gain a basic understanding of geologic time, the evidence for events in Earth's history, relative and absolute dating techniques, and the significance of the Geologic Time Scale.

- Teach about absolute dating: In this series of lessons for the high school and college levels, students learn the basic principles used to determine the age of rocks and fossils by using half-life in radioactive decay and stratigraphy.

- McCarthy, F. M. G., Patterson, R. T., Head, M. J., Riddick, N. L., Cumming, B. F., Hamilton, P. B., … and McAndrews, J. H. (2023). The varved succession of Crawford Lake, Milton, Ontario, Canada, as a candidate Global boundary Stratotype Section and Point for the Anthropocene series. The Anthropocene Review. 10: 146-176.

- Walker, M. J. C., Bauer, A. M., Edgeworth, M., Ellis, E. C., Finney, S. C., Gibbard, P. L., and Maslin, M. (2023). The Anthropocene is best understood as an ongoing, intensifying, diachronous event. Boreas. 53:1-3.

- Witze, A. (2024). Geologists reject the Anthropocene as Earth’s new epoch – after 15 years of debate. Nature. 627: 249-250.