Just as it is tempting to take natural selection to extremes, it is tempting to look for the evolutionary advantage of any trait of an organism — in other words, to see adaptations everywhere. Of course, the natural world is full of adaptations — but it is also full of traits that are not adaptations, and recognizing this is important. However, before we examine traits that are not adaptations, it will be useful to specifically define what an adaptation actually is and how we can determine whether or not a trait qualifies as an adaptation.

An adaptation is a feature produced by natural selection for its current function. Based on this definition we can make specific predictions (“If X is an adaptation for a particular function, then we’d predict that…”) and see if our predictions match our observations. As an example, we’ll consider the hypothesis: feathers are an adaptation for bird flight. Is the evidence consistent with this hypothesis? There are several relevant lines of evidence that must be examined:

Is it heritable?

Is it heritable?

If a trait has been shaped by natural selection, it must be genetically encoded — since natural selection cannot act on traits that don’t get passed on to offspring. Are feathers heritable? Yes. Baby birds grow up to have feathers like those of their parents.- Is it functional?

If a trait has been shaped by natural selection for a particular task, it must actually perform that task. Do feathers function to enable flight? In the case of bird flight, the answer is fairly obvious. Birds with feathers are able to fly and birds without feathers would not be able to. - Does it increase fitness?

Albatross images courtesy of Gerald and Buff Corsi, Focus on Nature, Inc. If a trait has been shaped by natural selection, it must increase the fitness of the organisms that have it — since natural selection only increases the frequency of traits that increase fitness. Are birds more fit with feathers than without? Yes. Birds without feathers aren’t going to leave as many offspring as those with feathers.

We could do experiments to test each of these criteria of adaptation. So far so good — the feature could have been shaped by natural selection. But we also have to look at historical questions about what was going on when it arose. Did feathers arise in the context of natural selection for flight?

How did it first evolve?

How did it first evolve?

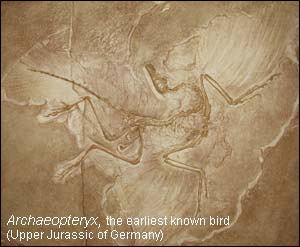

Did the trait arise when the current function arose? Did feathers arise when flying arose? The answer to this is probably no. The closest fossil relatives of birds, two-legged dinosaurs called theropods, appear to have sported feathers but could not fly.

This last question emphasizes the importance of understanding organisms’ history through fossils such as Archaeopteryx and reconstructed phylogenies. It is not enough to know that the feature is functional right now. We want to know what was happening when it first evolved, which often involves reconstructing the phylogeny of the organisms in which we are interested and determining the likely ancestral states of the characters.

Feathers meet three of the necessary requirements to be considered an adaptation for flight, but fail one of them. So the basic form of feathers is probably not an adaptation for flight even though it certainly serves that function now.