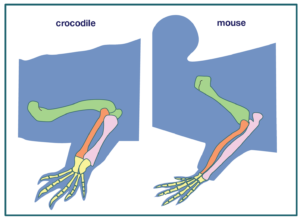

How do scientists figure out if a trait is a homology or not? Biologists use a few criteria to help them decide whether a shared morphological character (such as the presence of four limbs) is likely to be a homology. Here’s an example comparing mice and crocodiles:

Same basic structure

The same bones (though differently shaped) support the limbs of mice and crocodiles.

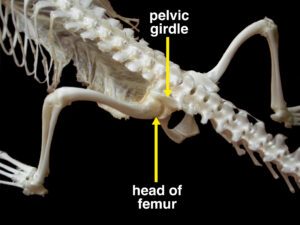

Same relationship to other features

The limb bones are connected to the skeleton in similar ways in different tetrapods. The joint between the femur and the pelvis has a ball-and-socket structure, as shown in this crocodile.

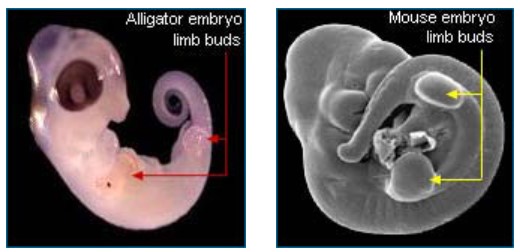

Same development

The limbs of all tetrapods develop from limb buds in similar ways.

Of course, these criteria don’t always apply — for example, two organisms might share a homologous gene, but the gene doesn’t really “develop.” However, these criteria are nonetheless useful. By studying the anatomy of a trait in living organisms and in fossils and by observing how the trait changes as an organism grows and develops, biologists can usually find out if a structure in two organisms is homologous or not.