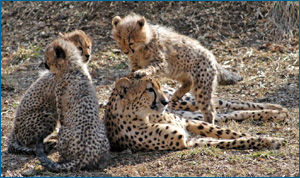

Philandering males, sneaking around behind their partners’ backs or openly canoodling, are a stock character on Animal Planet. Male lions, male chimps, and male elephant seals (along with many others) play the Casanovas, pairing up with multiple females. But now researchers have revealed that cheetahs buck this sexual stereotype. According to the May 2007 study, female cheetahs seem to be at least as promiscuous as their male counterparts. Females frequently mate with several different males while they are fertile and are then likely to bear a single litter of cubs fathered by multiple males — making many of the cubs within a single litter only half-siblings. This discovery has important implications for the conservation of these endangered animals. Though it conflicts with the idea that cheaters never prosper, evolutionary theory suggests that, in this case, cheating may be exactly what the doctor ordered…

Where's the evolution?

Conservation biologists are interested in cheetah cheating because it impacts the cheetah population’s level of genetic variation. Loosely, genetic variation is a measure of the genetic differences within a population. A population in which every individual has the same gene version (i.e., allele) at a particular location in the genome has less genetic variation for that gene than a population in which many individuals carry different gene versions at that location.

How did biologist Dada Gottelli and her colleagues at the Zoological Society of London figure out that female cheetahs were fooling around with so many different suitors? Cheetahs seem to be modest about mating. Biologists have rarely caught cheetahs “in the act,” but they have been able to pick up what cheetahs leave behind in their daily routine: poop. Feces contain traces of DNA. And cheetahs, like us, get half of their DNA from their mother and half from their father. So Gottelli’s team collected feces from mothers, their cubs, and potential fathers and then extracted and analyzed the DNA to perform paternity tests on the cubs.

Genetic variation is a key ingredient of evolution. Natural selection acts on the genetic variation present in a population to remove those variants that fail to produce offspring in a particular situation and spread those variants that are particularly good at producing offspring. A population with no genetic variation (in which every individual is genetically identical) cannot evolve in response to environmental or situational changes. If, for example, a genetically uniform population were exposed to a new pathogen and did not carry the gene versions necessary to fend off the disease, the population could face complete extinction. On the other hand, a population with high levels of genetic variation is much more likely to include at least a few individuals carrying the gene versions that provide protection from the pathogen — and, hence, to evolve in response to the new situation instead of going extinct. A population with low genetic variation is something of a sitting duck — vulnerable to all sorts of environmental changes that a more variable population could persist through.

And unfortunately, those are exactly the circumstances faced by cheetahs today. As a species, cheetahs have famously low levels of genetic variation. This can probably be attributed to a population bottleneck they experienced around 10,000 years ago, barely avoiding extinction at the end of the last ice age. However, the situation has worsened in modern times. Habitat encroachment and poaching have further reduce cheetah numbers, consequently snuffing out even more genetic variation and leaving cheetahs even more vulnerable to extinction.

Nevertheless, conservation biologists may have reason to hope that this genetic variation will not drain away as quickly as was thought — now that researchers from the Zoological Society of London have laid bare female cheetahs’ cheating hearts. The scientists have found that not only do female cheetahs bear single litters with multiple fathers, but those fathers are rarely near neighbors. Females seem to mate with individuals from far-flung regions, meaning that the cubs’ fathers are only distantly related to one another. Furthermore, female cheetahs don’t even return to the same males year after year: consecutive litters from the same mother all had different sets of fathers. In short, female cheetahs’ mating habits wind up getting genetic information from lots of different fathers into the next generation — and that helps preserve genetic variation!

In fact, the impact of multiple matings on genetic variation may help explain how the trait evolved in cheetahs in the first place. Biologists hypothesize that in an unpredictable environment, like the Serengeti, having variable offspring would have been advantageous to a female cheetah. Even if several of her cubs were killed by a new disease, succumbed to a novel environmental stress, or just didn’t have what it took to make a living in the Serengeti, a female with a variable litter could still hope that one of her cubs would have “the right stuff” to survive (shown in Scenario 1 below). Biologists refer to this as “bet-hedging” — not putting all your eggs (or in this case, cubs) in one basket. On the other hand, a female with a more genetically uniform litter might not have any of her cubs survive their dicey environment (Scenario 2 below). In this case the female who mated multiple times and had variable offspring would pass her genes on to the next generation, while the female who mated singly and had a more uniform litter would not. Over time, if this imbalance persisted, natural selection would favor females with genetically variable litters — and hence, females who engaged in multiple matings. So perhaps, what we humans perceive as promiscuity is actually an adaptation that allows female cheetahs to increase the odds of having at least one cub survive to pass on her genes.

While it’s certainly possible that the multiple mating strategy spread because of its impact on the genetic diversity within litters, biologists have also come up with two main alternative hypotheses to explain why multiple mating is common in cheetahs:

- Perhaps, multiple mating is really a strategy to avoid expending extra energy fending off would-be suitors. In other words, maybe females mate multiple times not because it ensures genetic variation in offspring, but because it’s so much easier than fighting off males right and left.

- Or perhaps, multiple mating evolved as a way to deter infanticide. In some big cats (and in many other species), males try to kill cubs that are not their own — a phenomenon known as infanticide. However, if a mother mates with many different males, it is more difficult for a male to tell whether or not a cub is his own — and the male would likely be deterred from killing the cub. This third hypothesis suggests that multiple mating was favored by natural selection because it discouraged infanticide against a female’s cubs, not because it increased the litter’s genetic variation. This third hypothesis fits with the observation that wild cheetah males seem to rarely (if ever) commit infanticide, though it is common in lions and other big cats.

Figuring out which of these three hypotheses (if any) is the right one will require further research. But regardless of what we learn about the evolutionary origins of multiple mating in female cheetahs, its evolutionary consequences today are clear. The fact that female cheetahs bear young with many different fathers helps preserve what little genetic variation the species has left — and could even buy us some time in our efforts conserve these endangered animals.

Primary literature:

- Gottelli, D., Wang, J., Bashir, S., and Durant, S. M. (2007). Genetic analysis reveals promiscuity among female cheetahs. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 274(1621):1993-2001. Read it »

- Menotti-Raymond, M., and O'Brien, S. J. (1993). Dating the genetic bottleneck of the African cheetah. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 90(8):3172-3176. Read it »

News articles:

- A news article on the research and its implications from the BBC News

- A friendly discussion of genetic variation in cheetahs from the Cheetah Conservation Fund

Understanding Evolution resources:

- A tutorial on genetic variation

- A quick explanation of how bottlenecks impact genetic variation

- A reader on the relevance of evolutionary theory to conservation

Background information from Understanding Global Change:

- Why is genetic variation so important to evolution?

- This article mentions two factors that contribute to low genetic variation in cheetahs. Describe those two factors.

- Read about bottlenecks and founder effects. In your own words, explain what a bottleneck is and how it affects a population’s level of genetic variation.

- What aspects of female cheetahs’ behavior impact the level of genetic variation among her cubs? How?

- Describe three hypotheses that biologists think might explain how multiple mating among female cheetahs evolved.

- This article describes how having cubs sired by many different males might be advantageous in an unpredictable environment. In that situation, a female who sought out males with many different traits might increase the odds that at least one of her cubs survives. How does the situation change if the cheetahs live in a predictable environment? Consider a female cheetah living in a highly predictable environment in which the next 20 years are unlikely to bring any significant environmental or other changes. For that cheetah, what would the ideal mating strategy be to ensure the survival of the maximum possible number of her cubs? Explain your reasoning.

- Teach about the role of variation in natural selection: In this lesson for grades 9-12, students explore the natural variations present in a variety of organisms by examining sunflower seeds and Wisconsin Fast PlantsTM to consider the role of heredity in natural selection.

- Teach about bottlenecks: In this lesson for grades 9-12, students achieve an understanding of the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium by using decks of playing cards without recourse to algebra. Extensions provided will facilitate the understanding of genetic drift, the founder effect, and bottlenecks.

- Teach about evolution and conservation: This lesson for grades 9-12 uses paper chromatography to simulate electrophoresis of DNA. The problem posed is to identify the genetic similarities among several sub-species of wolf in order to provide information for a conservation/breeding program.

- Gottelli, D., Wang, J., Bashir, S., and Durant, S. M. (2007). Genetic analysis reveals promiscuity among female cheetahs. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 274(1621):1993-2001.

- Menotti-Raymond, M., and O'Brien, S. J. (1993). Dating the genetic bottleneck of the African cheetah. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 90(8):3172-3176.