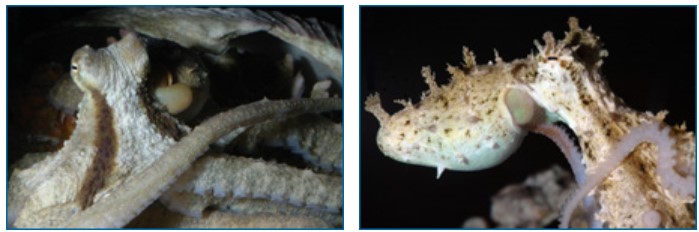

Long assumed to be loners, at least one octopus is now known to lead a complex love life. Last month, biologists Christine Huffard, Roy Caldwell, and Farnis Boneka reported on one of the first long term studies of octopus mating behavior in the wild. What they found out about the social life of the Indonesian octopus Abdopus aculeatus is the stuff of daytime television: jealousy, brawls, betrayal, sneaking around behind one another’s backs — if they had backs, that is — and, a soap-opera favorite, the open-ended question of paternity. The researchers discovered that males of this species are picky, preferentially bestowing their conjugal attentions on large females, and will guard a single female for up to 10 days (or more), mating with her frequently and fighting off other beaus that come calling — sometimes while still engaged in mating! (Having eight arms is a boon for multi-taskers.) But even a watchful eye and eight strong arms can’t guarantee that an aggressive guard won’t be cuckolded — especially given the sneaky tactics employed by some smaller males …

Where's the evolution?

Smaller male octopuses sometimes use a sneaky strategy to get their girl: female impersonation. While a large male guards a female in her den, displaying its telltale dark stripes that advertise its maleness, a smaller male might try to sneak a private rendezvous with the female by swimming low to the ground, hiding its masculine stripes and camouflaging itself, as females often do. Apparently not recognizing the sneaker as a rival, the guarding octopus may let him approach without attacking. The sneaking male hides behind a rock, extends his mating arm to the female, and, if lucky, accomplishes his mission. Sometimes, though, the gambit (“La-di-dah … Don’t worry about me — I’m just a female octopus passing through”) can work a bit too well: the researchers saw a guarding male set his sights on the sneaker male octopus passing though his territory and try to mate with “her.”

Why would a male change his stripes (literally), sneak around, and risk the unwelcome amorous advances of another male? Evolutionary advantage. All this guarding, aggression, repeat mating, and sneaking can be traced to one factor: paternity — who gets more genes into the next generation. Sexual selection favors any gene, anatomical structure, or behavior — no matter how bizarre — that provides a reproductive advantage. And animals have evolved some doozies when it comes to sneaky mating behavior:

- Sly male crickets produce no chirp themselves, but poach females attracted to another cricket’s call.

- Sneaker squid get love on the run by zipping up to a couple that has recently mated, rapidly depositing sperm in the female (in a quick, six-second affair!), and taking off again.

- Sneaky sand gobies hide in the sediment near a couple’s nest, waiting for an opportunity to slip into the nest to fertilize a few eggs on the sly before getting chased out by the resident male.

- Small dung beetles play the milkman calling at the back door. They excavate a side entrance into the tunnel system guarded by a larger dominant beetle, mate with the female chambered there, and try to slip away undetected.

- The smallest males of one marine isopod species make up for their small size with heavy investment in sperm. These little crustaceans sneak into the sponge commandeered as a love nest by a larger male and then dive bomb the mating couple, releasing a cloud of sperm at the critical moment.

In many organisms, sneakers get a leg up by impersonating females. These are just a few of the many animals that employ this tactic:

- Cross-dressing side-blotch lizards with the distinctive yellow throats of a receptive female lizard use their disguise to invade the territory of a rival male.

- Cuttlefish sneaker males take on female coloration, hide their masculine fourth arms, and hold the rest of their arms in the posture of an egg-laying female, in a bid to sidle up to a guarded female.

- Sneaky male salamanders take on the role of a female in a courtship dance and then destroy the sperm packet hopefully produced by the duped male.

- Bluegill sunfish with feminine color patterns can slip unnoticed into a guarded nest and fertilize the eggs there.

So while octopus cross-dressing may seem strange to us, it is just one example of a commonly employed strategy. Why has sneaking evolved over and over again in distantly related animal clades? The key to understanding the evolution of sneaky mating behavior is the other mating strategy present in most of the animals listed above: the mating monopoly. A monopolizing male attracts one or more females with his impressive coloration, large territory, willingness to care for eggs, or handsome sponge, in the case of the marine isopod, mates (often repeatedly), and tries to prevent his consorts from bestowing sexual favors on other males. If he is successful, he will father more eggs than his rivals. If he is not successful, the female may go on to mate with another male and the joys (or rather, genetic advantage) of fatherhood may shift to the rival. In this situation, any variant in male anatomy or behavior that makes its bearer a better guarder is likely to be passed on to all the extra offspring he fathers, allowing guarding behaviors to evolve and spread in the population via sexual selection. This monopolizing strategy is particularly successful — and particularly likely to evolve — when a mate-and-run strategy can’t assure 100% paternity and when females are relatively scarce.

The monopolizing strategy, however, has a major flaw. It is vulnerable to cheaters — males who don’t play by the strategic mate-guarding rules. Mutations that arise in a mate-guarding population and that allow their bearers to side-step the system and father offspring through an alternative strategy will be favored. This alternative strategy might involve female impersonation, hit-and-run mating, or something even stranger. It might arise through a series of mutations that cause their bearer to employ the alternative strategy or that allow their bearer to switch back and forth between mating strategies depending on the situation.

To see how these alternative strategies might get a foothold in a population with monopolizing males, think about it this way: When females are scarce and one male may monopolize several females at once, most males won’t get a chance to mate at all. A behavioral or physical variation (e.g., female impersonation, hit-and-run mating) that lets them father even a few offspring gives a big payoff in terms of genes in the next generation. And if those offspring also employ the non-traditional mating strategy and themselves manage to father a few offspring, the new mating strategy may become a permanent part of the population’s behavioral repertoire. So long as aggressive monopolizing males continue to father the most offspring, the new strategy won’t completely take over in the population.

The frequency with which we see sneaking behaviors across a wide range of distantly related animal species is testimony to their evolutionary success. Mate-guarding, territory control, and other aggressive strategies to ensure that one fathers a lot of offspring have evolved over and over again — and as they have, these systems have repeatedly been invaded by alternative mating strategies like sneaking. Though new discoveries about octopuses have revealed what may seem like unusual mating behaviors, they are actually tried-and-true evolutionary tricks — the result of an evolutionary mating game that has played out time and time again in many different animal groups.

Primary literature:

- Huffard, C. L., Caldwell, R. L., and Boneka, F. (2008). Mating behavior of Abdopus aculeatus (d'Orbigny 1834) (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae) in the wild. Marine Biology 154(2):353-362. Read it »

News articles:

- A complete description of the research from UC Berkeley News

- A description of how the research was carried out from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

- An article and video that describes how octopus and their relatives are able to change their appearance from The New York Times

Understanding Evolution resources:

- A brief review of sexual selection

- Background information on natural selection

- A case study of mantis shrimp evolution, which highlights the ability of these organisms to use different behavioral strategies in different situations to maximize their chances of survival

- Review the concept of sexual selection. Give at least three examples (not drawn from the article above) of the sorts of traits that sexual selection acts on.

- What octopus traits described above has sexual selection acted on? List at least two.

- Review the concepts of homology and analogy. Are female impersonation strategies in side-blotch lizards and bluegill sunfish likely homologies or analogies? Explain your reasoning.

- Read the comic strip Survival of the Sneakiest, which discusses the concept of evolutionary fitness. Explain what fitness means in terms of these octopuses. What traits contribute to fitness in these octopuses?

- This news brief describes traits which have been affected by sexual selection. Research and describe traits in three other organisms not mentioned in this article that have been affected by sexual selection.

- Teach about sexual selection and fitness: This comic strip for grades 6-12 follows the efforts of a male cricket as he tries to attract a mate, and in the process, debunks common myths about what it means to be evolutionarily "fit."

- Teach about another case in which evolution favors strategic flexibility: This article for grades 9-12 explains how a critically endangered parrot employs different reproductive strategies depending on the situation. Researchers are using evolutionary theory to guide their conservation efforts — with some impressive results!

- Huffard, C. L., Caldwell, R. L., and Boneka, F. (2008). Mating behavior of Abdopus aculeatus (d'Orbigny 1834) (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae) in the wild. Marine Biology 154(2):353-362.