2008 Stories

¿Decisiones de conservación difíciles? Pregúntale a la evolución

¿Si tu casa se incendiara, que es lo que te llevarías cuando estés huyendo? La decisión puede ser difícil entre juguetes de niños, álbumes de fotos y documentos importantes compitiendo por tu atención. Desafortunadamente, nos enfrentamos con una decisión difícil cuando tenemos que definir nuestros esfuerzos de conservación. Las actividades humanas podrían estar desencadenado la sexta extinción masiva de la Tierra. Cerca del 50% de todas las especies de animales y plantas podrían desaparecer durante nuestra vida. Mientras corremos para detener esta rápida perdida de biodiversidad, necesitaremos tomar decisiones, pero ¿dónde debemos concentrar nuestros esfuerzos? ¿En el tigre de Siberia, en la planta mas rara del mundo, en una fracción de selva Amazónica, o en un estuario amenazado que constituye el ‘semillero’ de la vida en el océano? Cualquiera sea nuestra decisión, no tenemos tiempo que perder. Cuanto antes tomemos la decisión sobre la preservación de especies, nuestros esfuerzos tendrán más probabilidad de éxito. Actualmente, nuevas investigaciones sugieren que la historia evolutiva nos puede ayudar a tomar estas decisiones de una manera más fácil.

Read more »Tough conservation choices? Ask evolution

If your home were on fire, what would you take with you when you fled? The choice could be tough, with childhood toys, photo albums, and important documents all vying for attention. Unfortunately, we face a similarly difficult decision when it comes to conservation. Human activities may be triggering the Earth’s sixth mass extinction. Nearly 50% of all animal and plant species could disappear within our lifetime. As we race to staunch this rapid loss of biodiversity, we’ll need to make choices, but where should we concentrate our efforts? On the Siberian tiger, the world’s rarest plant, a chunk of Amazonian rain forest, or a threatened estuary that serves as a nursery for ocean life? Whatever we decide, we don’t have time to waste. The sooner we take action on species preservation, the more likely those efforts are to succeed. Now, new research suggests that evolutionary history can help us make some of these difficult decisions more easily.

Read more »HIV’s not-so-ancient history

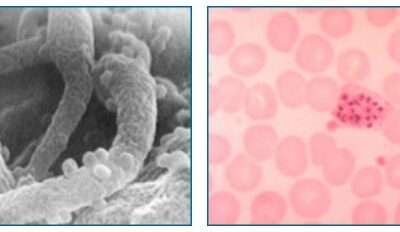

Ancient Egyptians described diabetes on a scrap of papyrus 3500 years ago. Two thousand four hundred years ago, Parkinson’s was first outlined in a Chinese medical text. And Chinese, Greek, Roman, and Indian civilizations had all recognized malaria long before we had microscopes to observe the parasites that cause the disease. By comparison, HIV is a distinctly modern disease. It was first described in 1981, and drugs to treat it weren’t available until 1987. But for how long before its discovery did HIV lurk unnoticed in human populations? New research paints a clearer picture of when (and how) HIV got its start. Last month, an international group of researchers reported on fragments of the HIV virus discovered in a preserved, 1960 tissue sample from a woman living in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo). The sample, along with many other lines of evidence, confirms that HIV’s roots burrow much deeper than our first recognition of the virus — back to the turn of the century.

Read more »Ghosts of epidemics past

Diseases that pose global health threats — like HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis — regularly make the news. Last month, for example, saw reports that HIV infection rates in the US are up, that malaria statistics worldwide are down, and that the distribution of medicines to treat the three diseases had improved. Diseases with such epidemic proportions tend to make us focus on the near future: Regardless of how we wound up in this situation, what can we do now to prevent future infections and deaths? But sometimes — especially in the case of populations coevolving with disease pathogens — a glimpse of our evolutionary past, can be surprisingly informative.

Read more »Evolution down under

If you’ve seen images of it on the news or in the paper, you won’t soon forget it. Devil facial tumor disease (DFTD) causes bulging cancerous lumps and lesions to erupt around the face and neck — often causing enough deformation to make seeing or eating difficult. While it may be something of a relief to learn that this fatal disease affects only Tasmanian devils, marsupial carnivores of Tasmania, its impact on that population has been staggering. The disease was first observed by a wildlife photographer in 1996 and, since then, has reduced the total devil population by half — and in some areas, by as much as 90%! Tasmanian devils were recently listed as endangered and could become extinct in the wild in the next few decades. This summer, however, scientists reported that devils may be responding to DFTD by breeding earlier — before they are likely to be killed by the disease. This change could help the species survive longer, but is it an evolutionary one?

Read more »Juego evolutivo de citas y apareamiento

Largamente asumidos como solitarios, al menos una especie de pulpo lleva una compleja vida amorosa. El mes pasado, los biólogos Christine Huffard, Roy Caldwell y Farnis Boneka reportaron los resultados de los primeros estudios a largo plazo sobre el comportamiento de apareamiento de pulpos en la naturaleza. Lo que han encontrado acerca de la vida social del pulpo de Indonesia, Abdopus aculeatus, parece parte de un programa de televisión de la tarde: celos, peleas, traición, espiar a escondidas por la espalda — eso si los pulpos tuvieran espalda — y, el favorito de las novelas, la pregunta siempre abierta de la cuestión de paternidad. Los científicos descubrieron que los machos de esta especie son quisquillosos, ofrecen su atención conyugal preferentemente a hembras grandes y custodian a una única hembra por hasta 10 días (o más), se aparean con ella frecuentemente y pelean contra los pretendientes que se acerquen — ¡a veces mientras están todavía apareándose! (tener ocho brazos es un gran beneficio para los que son multi-tareas). Pero aun un ojo vigilante y ocho fuertes brazos no pueden garantizar que una guardia agresiva no sea engañada — especialmente dada las tácticas furtivas empleadas por machos más pequeños …

Read more »Evolution’s dating and mating game

Long assumed to be loners, at least one octopus is now known to lead a complex love life. Last month, biologists Christine Huffard, Roy Caldwell, and Farnis Boneka reported on one of the first long term studies of octopus mating behavior in the wild. What they found out about the social life of the Indonesian octopus Abdopus aculeatus is the stuff of daytime television: jealousy, brawls, betrayal, sneaking around behind one another’s backs — if they had backs, that is — and, a soap-opera favorite, the open-ended question of paternity. The researchers discovered that males of this species are picky, preferentially bestowing their conjugal attentions on large females, and will guard a single female for up to 10 days (or more), mating with her frequently and fighting off other beaus that come calling — sometimes while still engaged in mating! (Having eight arms is a boon for multi-taskers.) But even a watchful eye and eight strong arms can’t guarantee that an aggressive guard won’t be cuckolded — especially given the sneaky tactics employed by some smaller males …

Read more »Superbug, super-fast evolution

Fascination with tiny microbes bearing long, difficult-to-pronounce names is often reserved for biology classrooms — unless of course the bug in question threatens human health. MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) now contributes to more US deaths than does HIV, and as its threat level has risen, so has the attention lavished on it by the media. At this point, almost any move the bug makes is likely to show up in your local paper. Last month saw reporting on studies of hospital screening for MRSA (which came up with conflicting results), stories on MRSA outbreaks (involving both real and false alarms), and media flurries over the finding that humans and their pets can share the infection with one another. Why is this bug so frightening? The answer is an evolutionary one.

Read more »The new shrew that’s not

Not a shrew, that is. If you flipped through the newspaper’s Science and Technology section last month, you might have spotted this adorable imposter: big eyes, dainty feet, and a long, flexible snout resembling an anteater’s or an elephant’s. Formally known as Rhynchocyon udzungwensis, the giant elephant shrew made the news because it is fuzzy, photogenic, and new to science. While thousands of insect species are discovered each year, mammal species not yet in the scientific record (especially ones the size of a hefty squirrel, like R. udzungwensis) are a rarity. Most elephant shrew species were first described in the 1800s by scientists who classified them as shrews because of obvious physical similarities. But recent genetic evidence has confirmed that elephant shrews are not shrews at all…

Read more »Evolution in the fast lane?

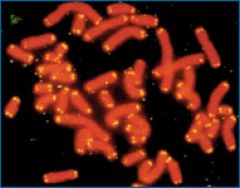

The question of whether we, as a species, are still evolving, sometimes inspires visions of a new-and-improved Homo sapiens, complete with super-sized brain, disease-resistance, and the ability to withstand the pollutants and toxins common in a techno-centric future. While science fiction writers have come up with imaginative and entertaining answers to the question of how humans might be evolving, the responses of the scientific community have been more staid. Perhaps, they’ve suggested, some genes for withstanding epidemic disease are currently on the rise. However, with the improved genetic sequencing technologies that have come online in the last decade, many biologists are now prepared to offer more specific hypotheses as to how species are changing. Recently, a team of researchers led by scientists at the University of Utah announced that they’d scanned the genomes of 270 people and found evidence that humans are not only evolving — but that we’ve been adapting at an unusually rapid pace — at least on evolutionary timescales. The group has also made the controversial suggestion that human populations on different continents are evolving away from one another. However, a look at the evolutionary biology behind the headlines highlights some limits of this research.

Read more »