The genius of Darwin (left), the way in which he suddenly turned all of biology upside down in 1859 with the publication of the Origin of Species, can sometimes give the misleading impression that the theory of evolution sprang from his forehead fully formed without any precedent in scientific history. But as earlier chapters in this history have shown, the raw material for Darwin’s theory had been known for decades. Geologists and paleontologists had made a compelling case that life had been on Earth for a long time, that it had changed over that time, and that many species had become extinct. At the same time, embryologists and other naturalists studying living animals in the early 1800s had discovered, sometimes unwittingly, much of the best evidence for Darwin’s theory.

The genius of Darwin (left), the way in which he suddenly turned all of biology upside down in 1859 with the publication of the Origin of Species, can sometimes give the misleading impression that the theory of evolution sprang from his forehead fully formed without any precedent in scientific history. But as earlier chapters in this history have shown, the raw material for Darwin’s theory had been known for decades. Geologists and paleontologists had made a compelling case that life had been on Earth for a long time, that it had changed over that time, and that many species had become extinct. At the same time, embryologists and other naturalists studying living animals in the early 1800s had discovered, sometimes unwittingly, much of the best evidence for Darwin’s theory.

Pre-Darwinian ideas about evolution

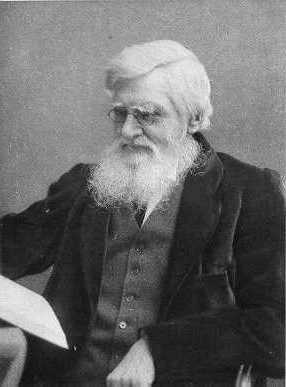

It was Darwin’s genius both to show how all this evidence favored the evolution of species from a common ancestor and to offer a plausible mechanism by which life might evolve. Lamarck and others had promoted evolutionary theories, but in order to explain just how life changed, they depended on speculation. Typically, they claimed that evolution was guided by some long-term trend. Lamarck, for example, thought that life strove over time to rise from simple single-celled forms to complex ones. Many German biologists conceived of life evolving according to predetermined rules, in the same way an embryo develops in the womb. But in the mid-1800s, Darwin and the British biologist Alfred Russel Wallace independently conceived of a natural, even observable, way for life to change: a process Darwin called natural selection.

The pressure of population growth

Interestingly, Darwin and Wallace found their inspiration in economics. An English parson named Thomas Malthus published a book in 1797 called Essay on the Principle of Population in which he warned his fellow Englishmen that most policies designed to help the poor were doomed because of the relentless pressure of population growth. A nation could easily double its population in a few decades, leading to famine and misery for all.

When Darwin and Wallace read Malthus, it occurred to both of them that animals and plants should also be experiencing the same population pressure. It should take very little time for the world to be knee-deep in beetles or earthworms. But the world is not overrun with them, or any other species, because they cannot reproduce to their full potential. Many die before they become adults. They are vulnerable to droughts and cold winters and other environmental assaults. And their food supply, like that of a nation, is not infinite. Individuals must compete, albeit unconsciously, for what little food there is.

Selection of traits

In this struggle for existence, survival and reproduction do not come down to pure chance. Darwin and Wallace both realized that if an animal has some trait that helps it to withstand the elements or to breed more successfully, it may leave more offspring behind than others. On average, the trait will become more common in the following generation, and the generation after that.

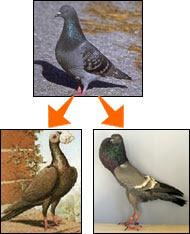

As Darwin wrestled with natural selection he spent a great deal of time with pigeon breeders, learning their methods. He found their work to be an analogy for evolution. A pigeon breeder selected individual birds to reproduce in order to produce a neck ruffle. Similarly, nature unconsciously “selects” individuals better suited to surviving their local conditions. Given enough time, Darwin and Wallace argued, natural selection might produce new types of body parts, from wings to eyes.

Darwin and Wallace develop similar theory

Darwin began formulating his theory of natural selection in the late 1830s but he went on working quietly on it for twenty years. He wanted to amass a wealth of evidence before publicly presenting his idea. During those years he corresponded briefly with Wallace (right), who was exploring the wildlife of South America and Asia. Wallace supplied Darwin with birds for his studies and decided to seek Darwin’s help in publishing his own ideas on evolution. He sent Darwin his theory in 1858, which, to Darwin’s shock, nearly replicated Darwin’s own.

Charles Lyell and Joseph Dalton Hooker arranged for both Darwin’s and Wallace’s theories to be presented to a meeting of the Linnaean Society in 1858. Darwin had been working on a major book on evolution and used that to develop On the Origins of Species, which was published in 1859. Wallace, on the other hand, continued his travels and focused his study on the importance of biogeography.

The book was not only a best seller but also one of the most influential scientific books of all time. Yet it took time for its full argument to take hold. Within a few decades, most scientists accepted that evolution and the descent of species from common ancestors were real. But natural selection had a harder time finding acceptance. In the late 1800s many scientists who called themselves Darwinists actually preferred a Lamarckian explanation for the way life changed over time. It would take the discovery of genes and mutations in the twentieth century to make natural selection not just attractive as an explanation, but unavoidable.

- Read more about the process of natural selection in Evolution 101.

- Go right to the source and read Darwin's On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.

- Explore the American Museum of Natural History's Darwin exhibit to learn more about his life and how his ideas transformed our understanding of the living world.