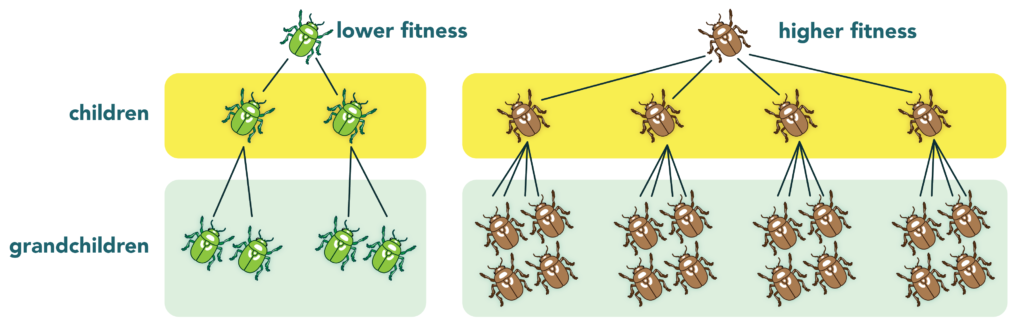

Evolutionary biologists use the word fitness to describe how good a particular genotype is at leaving offspring in the next generation relative to other genotypes. So if brown beetles consistently leave more offspring than green beetles because of their color, you’d say that the brown beetles had a higher fitness. In evolution, fitness is about success at surviving and reproducing, not about exercise and strength.

Of course, fitness is a relative thing. A genotype’s fitness depends on the environment in which the organism lives. The fittest genotype during an ice age, for example, is probably not the fittest genotype once the ice age is over.

Fitness is a handy concept because it lumps everything that matters to natural selection (survival, mate-finding, reproduction) into one idea. The fittest individual is not necessarily the strongest, fastest, or biggest. A genotype’s fitness includes its ability to survive, find a mate, produce offspring — and ultimately leave its genes in the next generation.

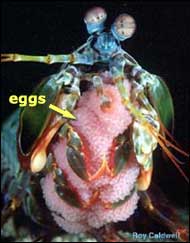

Caring for your offspring (above left), producing thousands of young — many of whom won’t survive (above right) — and sporting fancy feathers that attract females (left) are a burden to the health and survival of the parent. These strategies do, however, increase fitness because they help the parents get more of their offspring into the next generation.

We tend to think of natural selection acting on survival ability — but, as the concept of fitness shows, that’s only half the story. When natural selection acts on mate-finding and reproductive behavior, biologists call it sexual selection.

Learn more about fitness in context:

- Survival of the sneakiest, a comic strip with discussion questions.

- Conserving the kakapo, a news brief with discussion questions.

- Evolution from a virus's view, a news brief with discussion questions.

- Killer whales get a fitness boost after their offspring are grown, a news brief with discussion questions.

Reviewed and updated, June 2020.