How does life begin? At the dawn of the nineteenth century, naturalists were staring through microscopes in hopes of finding the answer. In the process, they discovered some peculiar things about embryos. A chicken may look very different from a fish, but their embryos share some striking similarities. They both develop from a single cell into tube-shaped bodies, for example. They share many traits early on, such as a set of arching blood vessels in their necks. In fish, the vessels retain this arrangement, so that they can take in oxygen from their gills. But in chickens—as well as mammals like us, amphibians, and reptiles—they are reworked into a very different anatomy suited to getting oxygen through lungs.

In Germany, where much of this study was done, some researchers claimed that these similarities were signs that life formed a series from simple forms to lofty ones (the loftiest being, of course, ourselves). As embryos we pass through this series—we “recapitulate” it—on our way to becoming human. We started out life as a worm, became a fish (complete with gill arches), a reptile, and so on. Some naturalists even claimed that recapitulation was evidence that life had changed through time, as higher and higher forms emerged on Earth.

von Baer: Recapitulation is kaput

In 1828, the Estonian-born embryologist Karl von Baer launched a withering attack on recapitulation. A careful look at embryos revealed that it was impossible to arrange them in any meaningful series. From the earliest stages, vertebrates all share an anatomy that invertebrates such as insects or worms never acquire. And even within vertebrates, there are facts that clash with recapitulation. A human does not develop a wing or a hoof before forming a hand—humans, birds, and horses all begin with limb buds, which then diverge into different adult limbs.

Compelling evidence for evolution

Baer was no fan of evolution, and so it was much to his chagrin that Darwin used his work to provide some of the most compelling evidence in Origin of Species. A species inherits its developmental program from its ancestors, and so two closely related species would be expected to have similar—but not necessarily identical—embryos. Over time, as lineages evolve further away from each other, natural selection modifies their embryos in various ways, but some vestiges of their common ancestry survive. That’s why we still bear a limited resemblance to fish in our early embryonic stages. Darwin did not argue that life was arrayed in a linear series from lower to higher; instead, he saw life branching like a tree as new species emerged.That branching was reflected in the similar paths of development that ultimately produced hooves, claws, and hands.

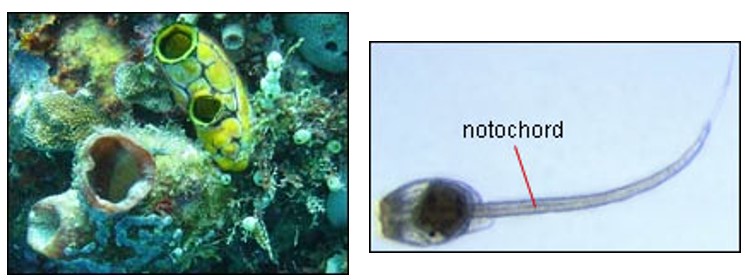

What about Baer’s claim that vertebrates couldn’t be aligned with invertebrate animals? Embryologists working in the mid-1800s showed that the division was not unbridgeable. Some invertebrates known as sea squirts, for example, develop the same kind of stiff rod that vertebrates form in their back as embryos, known as a notochord. In vertebrates the notochord turns into the disks between the vertebrae. If this were in fact a sign of common ancestry, you’d expect sea squirts to be close relatives of vertebrates. And indeed, studies on the DNA of sea squirts show that they are in fact the closest invertebrate relatives of vertebrates yet known.