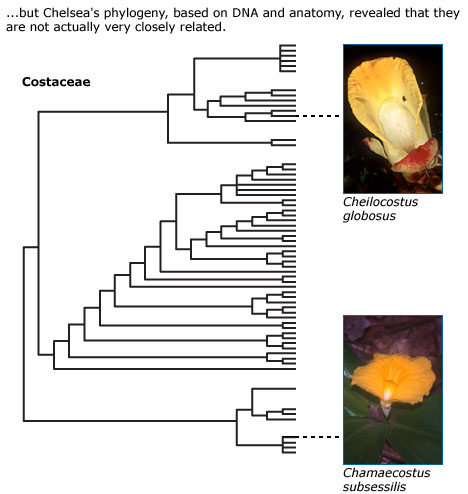

The phylogeny made one thing perfectly clear: the classification of Costaceae was seriously outdated. Today biologists try to classify organisms according to their evolutionary history so that species with close evolutionary relationships are grouped together. In this system, organisms are sorted into clades — groups that contain an evolutionary ancestor and all the species that descended from that ancestor — and those clades are given names. An ideal classification scheme, in which species are grouped and named according to their evolutionary relatedness, might look like that shown below.

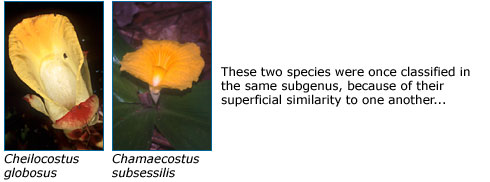

The original classification of Costaceae, on the other hand, reflected superficial similarity — largely based on the appearance of their flowers — instead of the deep structural and genetic similarities that reflect common ancestry. For example, Cheilocostus globosus and Chamaecostus subsessilis (shown below) had originally both been placed in the same subgenus of Costus. However, according to the phylogeny that Chelsea built based on DNA and anatomy, these species are not very closely related at all — despite their similar appearances. After studying their phylogeny, Chelsea modernized the classification of these plants so that their names would reflect their evolutionary relatedness.

Dig deeper: learn more about phylogenies and phylogenetic classification.

Get tips for using research profiles, like this one, with your students.