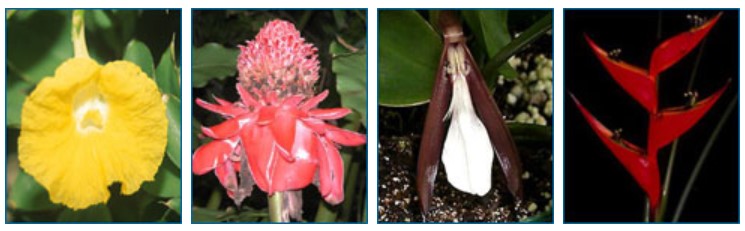

Gingers are a diverse group of approximately 3,000 plant species, including the bird of paradise plant, banana plants, and the plant that we typically call “ginger” with its spicy underground stem (i.e. rhizome). While we know many of these plants for their fruits (e.g., bananas) or other edible parts (e.g., ginger), the gingers are also known for the incredible variety of their flowers, which have evolved appearances that run the gamut from standard yellow flowers, to red bottlebrush masses, to dark and dangerous-looking orchid-types, to heliconia’s red “horns.” Chelsea is particularly interested in a group of gingers called the spiral gingers, or the Costaceae.

How did all this diversity arise? Answering this question begins with figuring out the phylogeny, or evolutionary tree, of these plants; as Chelsea puts it, “Every single mechanism for understanding diversification has to start with a phylogenetic framework.”

To build a phylogeny for the Costaceae, Chelsea studied the anatomy of the plants, obtained their DNA sequences, and used these lines of evidence to reconstruct the evolutionary relationships of the plant species. The process of reconstructing a phylogeny can be complex. Researchers examine several types of data in order to figure out which evolutionary relationships are best supported by the evidence. The resulting phylogeny is a hypothesis about the evolutionary relationships between the organisms — a hypothesis that is well supported by the data. The phylogeny that Chelsea reconstructed for her plants is shown below.

Find out more about how phylogenies are built.

Get tips for using research profiles, like this one, with your students.