Before Jackson started graduate school, he had worked as a curator at the National Museum in Tanzania, which houses some particularly important fossils from Olduvai Gorge, including the 1.8 million year old skull, jaw, hand bones, and foot of Homo habilis discovered by the Leakeys. Jackson was familiar with these fossils and the obvious tooth marks they bore from his time at the museum. In 1990, paleontologists Su Solomon and Iain Davidson from Australia had hypothesized that the marks on the skull of H. habilis were the result of a crocodile attack2 but had not done a formal analysis of the sort of traces a crocodile tooth would leave. Jackson initially accepted this interpretation of the evidence, but while doing his own feeding experiments with crocodiles, he started to reevaluate that position.

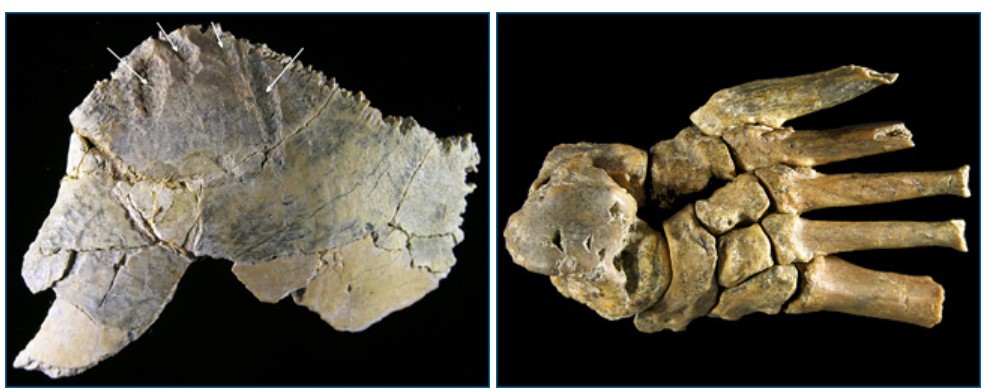

Since Jackson was doing the feeding experiments near Dar es Salaam, it was a short trip to the museum to have another look at the H. habilis fossils. He carefully examined the marks on the fossil and compared them with crocodile tooth marks. The marks on the skull specimen were broad and shallow, and didn’t look like any of the crocodile marks he’d documented; they looked more like those made by a leopard-like carnivore. “I realized that was not a croc,” says Jackson. “But the foot — those punctures and the contexts of the marks really looked like what I’d seen in some of my bones!”

The marks on the foot intrigued Jackson because this specimen was the subject of a bold hypothesis. In the 1980s, an American paleontologist, Professor Randy Susman, had been studying the same fossils, comparing the H. habilis foot fossil to a hominid leg fossil (a tibia) that had been found at a nearby site at Olduvai. The foot and leg bones both came from the left appendage and were of a size and shape that could have fit together, leading Susman to hypothesize that the two bones belonged to the same individual.3

Jackson realized that crocodile predation represented another line of evidence that might support Susman’s hypothesis: “I thought, if the two bones were from the same person, and if the foot bone had crocodile tooth marks, then the articulating tibia should also have crocodile tooth marks — just because of the anatomy of the human body and the way that crocodiles capture and feed on their prey. There’s no way the crocodile could have bitten the foot in the way it did without also marking the distal end of the tibia.”

The tibia was housed in a Kenyan museum, so Jackson went to Nairobi to see it for himself. Confirming his expectation, the leg bone bore tooth marks, as well as damage that appeared to have been inflicted by crocodiles and a leopard-sized mammalian carnivore. And when Jackson and his colleagues returned to Olduvai and reexamined the sediments in which the H. habilis foot was found, it was clear that the foot had come from an ancient wetland environment that had been occupied by crocodiles. Everything seemed to be fitting together and pointed toward the same explanation…

2 Davidson, I., and S. Solomon. 1990. Was OH 7 the victim of a crocodile Attack? Pp. 197-206 in S. Solomon, I. Davidson, and D. Watson (eds.), Problem Solving in Taphonomy: Archaeological and Palaeontological Studies from Europe, Africa and Oceania. Tempus, St. Lucia, Queensland.

3 Susman, R.L., and J.T. Stern. 1982. Functional morphology of Homo habilis. Science 217:931-934.