Sexual selection is a “special case” of natural selection. Sexual selection acts on an organism’s ability to obtain (often by any means necessary!) or successfully copulate with a mate.

Sexual selection has shaped many extreme adaptations that help organisms find mates: peacocks (top left) maintain elaborate tails, elephant seals (top right) fight over territories, fruit flies perform dances, and some species deliver persuasive gifts. After all, what female Mormon cricket (bottom right) could resist the gift of a juicy sperm-packet? Going to even more extreme lengths, the male redback spider (bottom left) literally flings itself into the jaws of death in order to mate successfully.

Sexual selection is even powerful enough to produce features that are harmful to the individual’s survival. For example, extravagant and colorful tail feathers or fins are likely to attract predators as well as interested members of the opposite sex.

Digging Data

Digging Data

The venomous female redback spider – also known as the Australian black widow – poses a danger to humans … and to male redback spiders, which are often eaten by their mates. Males seem to go out of their way to make this happen, flipping themselves over and presenting their abdomens to the female while mating. This behavior might at first seem like one that selection would act against. After all, how could risking one’s life be adaptive? Remember that evolutionary fitness is about getting genes into the next generation, not just survival. Perhaps this extreme behavior is favored by sexual selection because it gives males a fitness boost. But what advantage could it offer? Biologist Maydianne Andrade made observations and designed a set of experiments to find out

Background

Male redback spiders deliver their sperm to females using specialized mouthparts. If the female is hungry, she will eat the male during the mating process. In the wild, this happens about 65% of the time. Females often mate with more than one male and can store sperm (sometimes for years!) to use later. Females produce multiple egg sacs throughout their lives, each of which can contain hundreds of eggs. Different eggs in a single egg sac may be fertilized by sperm from different fathers.

Hypotheses

There are several explanations that could lead to the evolution of males’ risky mating behavior:

- The nutrients provided by eating the male are passed on to the eggs/offspring. In this scenario, sexual selection would favor males that offer themselves up as a meal because those males would leave behind more or perhaps more robust eggs that are more likely to hatch into live spiderlings.

- Eating one’s mate decreases the likelihood that a female will mate again with another male. In this scenario, sexual selection would favor the risky behavior because males that allow themselves to be eaten would prevent later matings and, thus, would father more of a female’s brood.

- Males that are eaten mate for longer and so fertilize more of a female’s eggs. Perhaps eating a mate takes time, or perhaps females simply allow mates that offer up their abdomens to mate longer. In either case, evolution would favor the risky behavior if it allows a male to father more of the female’s offspring than do males that do not offer up a snack.

Maydianne made observations and carried out experiments to test each of these hypotheses.

Data

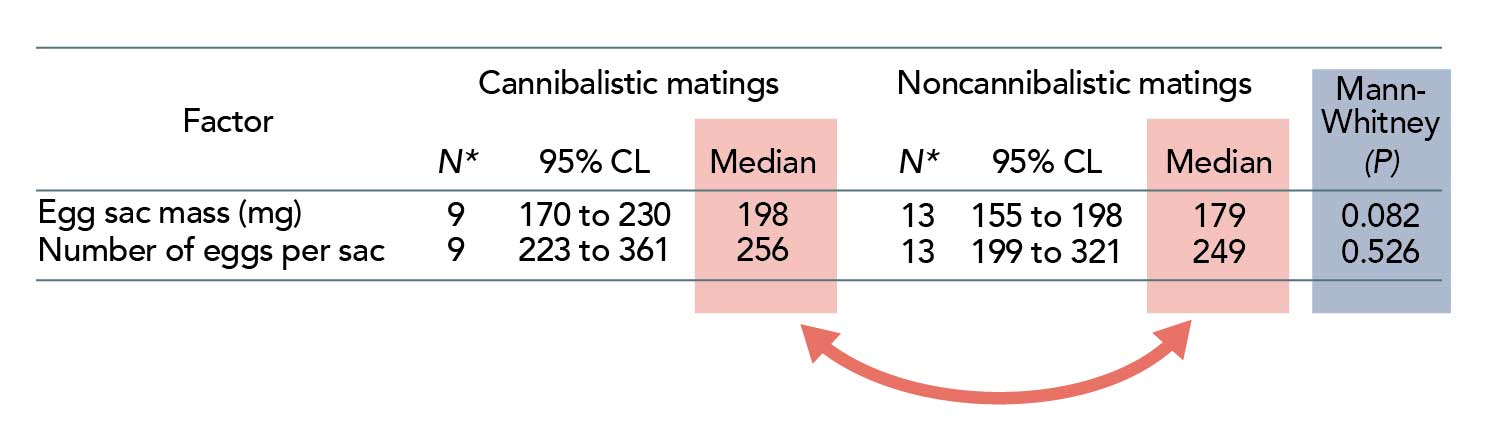

Hypothesis 1 – Does a female’s “snack” give a boost to her eggs? In captive redbacks in the lab, Maydianne compared the number of eggs in and weight of egg sacs from matings where the male was eaten to those from matings in which he was not:

The 95% CL (confidence level) is the range within which the true value is likely to fall (i.e., in 100 cases with similar data, the true value is within this range in 95 of those cases). The Mann-Whitney test looks at whether two samples are likely to come from sources with the same median. The p value of this test indicates the probability that the two samples come from sources with the same median (i.e. are *not* different).

There is a very slight trend towards more eggs and heavier egg sacs resulting from cannibalistic matings (as seen by comparing the pink highlighted medians), but this difference is not significant (blue highlighted box). This contradicts hypothesis 1.

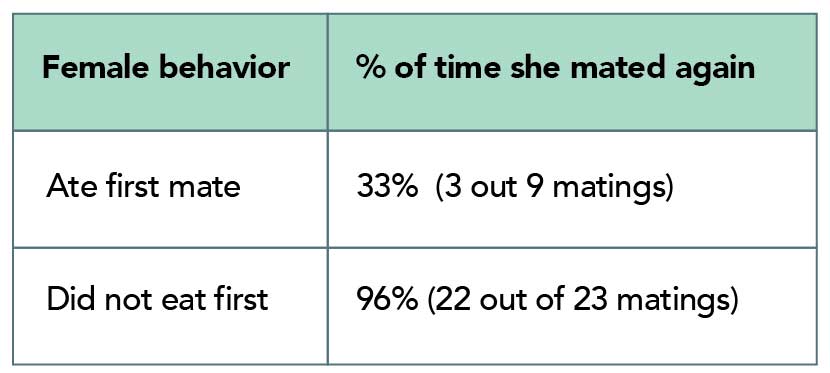

Hypothesis 2 – Did eating a mate decrease the odds that a female would mate again with a different male? In the lab, Maydianne observed females’ first and subsequent matings and collected the following data:

Apparently, skipping breakfast (not eating one’s first mate) leaves female redbacks interested in a snack (one’s second mate)! These data support hypothesis 2.

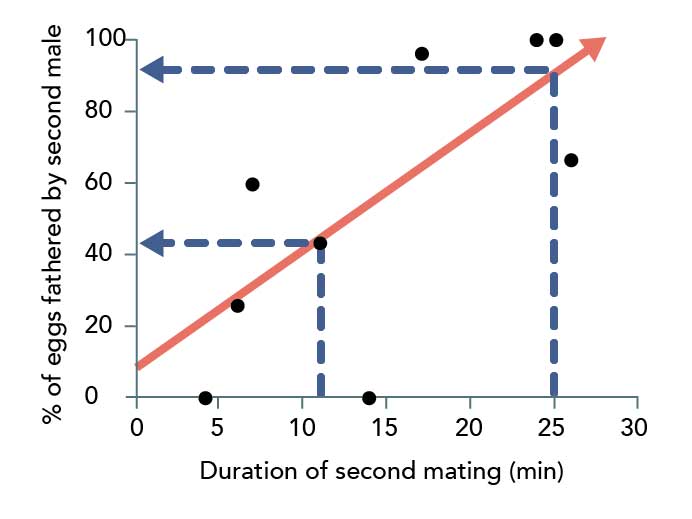

Hypothesis 3 – Does self-sacrifice pay off with paternity? Maydianne also observed and timed matings in the lab, and then determined the paternity of the eggs that the female ultimately produced. Maydianne focused on the second male to mate with a female. She thought that a male allowing himself to be eaten might pay off in terms of paternity, particularly if he were able to mate for longer if cannibalized. She observed that cannibalized second males mate for much longer (a median of 25 minutes) than second males that are not eaten (and mate for a median of just 11 minutes). Here are data from 10 matings:

For each mating, she plotted a point (black dot) representing how long the second mating took (x-axis) and the fraction of the eggs in the sac fathered by that second male (y-axis). The data are pretty clear: longer mating is associated with more paternity. This is shown by the upward slope of the regression line (red arrow). The dotted lines and blue arrows show how much a second male can improve his fitness by fathering more eggs if he is eaten and mates for 25 min, as opposed to surviving and mating just 11 minutes. Based on these data, we’d expect self-sacrificers to father 92% of eggs versus just 45% for survivors. These data support hypothesis 3.

Sexual selection seems to be shaping male redback spiders’ self-sacrificial mating behavior, not through the nutrition provided by eating one’s mate, but through its effect on fertilization rate and female behavior. But note the small sample sizes. More data might make us more confident in this interpretation.

Stepping into science

Maydianne started doing research as an undergraduate. She got interested in studying invertebrates, since she could mimic their natural environments in the lab. She was particularly curious to learn what males contribute to their mates and offspring – so when her Master’s advisor told her about the strange behavior of male redback spiders, she was intrigued. And when she realized she’d be able to escape the Canadian winter and visit sunny Australia, she was sold!

Teachers can use the following resources to build a lesson sequence around sexual selection and redback spiders for the high school or college levels.

- 2-minute video from the Australian Academy of Science introducing the phenomenon of sexual cannibalism in redback spiders

- Student reading with comprehension questions (.docx download)

- Student reading with comprehension and data interpretation questions (.docx download)

- A clicker-based case study on sexual cannibalism in the Australian redback spider, from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science

- Scientist Spotlight reading and worksheet on Maydianne (requires site registration)

- A CBC audio interview with Maydianne, including discussion of spiders, unconscious bias, imposter syndrome, and the burden carried by Black scientists

- A NOVA interview with Maydianne, along with audio highlights

For answer keys to the worksheets above, teachers can email UEKeys@berkeley.edu from a school email address and must be verifiably employed as an educator at that school.

The following Data Nugget activities for middle and high school students offer students opportunities to analyze data on sexual selection in other animal systems:

Data and error analysis in science: A beginner’s guide – includes background information on median and confidence intervals

Nonparametric tests – includes background information on the Mann-Whitney test

The linear regression test – background information

Andrade, M. C., B., (1996). Sexual selection for male sacrifice in the Australian redback spider. Science. 271: 70-72.

Reviewed and updated, June 2020.