Sometimes a dwindling population needs a jumpstart. And for threatened or endangered fish populations, that often means supplementing wild populations with hatchery-raised fish. But this conservation tactic is not risk-free: hatchery fish populations may evolve in different directions from wild populations — and hatchery genes may be dangerous for wild populations.

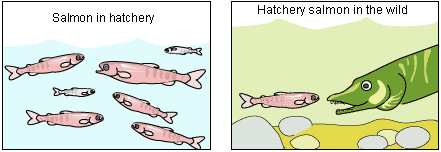

In the wild, fish with good genes for river-life survive and produce more offspring — and in hatcheries, fish with good genes for hatchery-life survive and produce more offspring. So hatchery populations evolve with different characteristics from wild populations. For example, hatcheries may unintentionally artificially select for different breeding behaviors and different body shape and color — traits that reduce a fish’s ability to survive and reproduce in the wild.

And therein lies the danger of supplementing wild populations with hatchery fish. Michael Ford of the National Marine Fisheries Service used a computer model to show that captive-bred fish can introduce gene variants into wild populations — and those gene variants may reduce survival and reproduction in the wild. Further, his results suggest that “quick fixes” — like adding wild fish to hatcheries each generation — may not do much to counteract the risk. However, Ford points out that hatchery managers may be able to control the evolution of captive populations by avoiding accidental artificial selection in captivity — that means that hatcheries should try to mimic only the selection pressures that wild populations experience by, for example, using more natural breeding and rearing methods.

Ford’s model of evolution in fish populations necessarily makes some simplifying assumptions, but other biologists are working to find out if predictions like Ford’s are accurate. Among others, University of Oregon researcher Michael Lynch is studying wild steelhead to find out how supplementing their numbers with hatchery fish affects their survival and reproduction. Advances in genetics have only recently made these studies possible — researchers should soon learn the results of these natural experiments in evolution, and whether hatchery genes pose a threat to wild fish populations.