Huntington’s chorea is a devastating human genetic disease. A close look at its genetic origins and evolutionary history explains its persistence and points to a potential solution to this population-level problem.

People who inherit this genetic disease have an abnormal dominant allele that disrupts the function of their nerve cells, slowly eroding their control over their bodies and minds and ultimately leading to death. In the fishing villages located near Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela (see map at left), there are more people with Huntington’s disease than anywhere else in the world. In some villages, more than half the people may develop the disease.1

People who inherit this genetic disease have an abnormal dominant allele that disrupts the function of their nerve cells, slowly eroding their control over their bodies and minds and ultimately leading to death. In the fishing villages located near Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela (see map at left), there are more people with Huntington’s disease than anywhere else in the world. In some villages, more than half the people may develop the disease.1

How is it possible that such a devastating genetic disease is so common in some populations? Shouldn’t natural selection remove genetic defects from human populations? Research on the evolutionary genetics of this disease suggests that there are two main reasons for the persistence of Huntington’s in human populations: mutation coupled with weak selection.

The diagram at right shows how the Huntington’s allele is passed down. Since it is the dominant allele, individuals with just one parent with Huntingtons’s chorea have a 50-50 chance of developing the disease themselves.

The diagram at right shows how the Huntington’s allele is passed down. Since it is the dominant allele, individuals with just one parent with Huntingtons’s chorea have a 50-50 chance of developing the disease themselves.

Mutation

In 1993, a collaborative research group discovered the culprit responsible for Huntington’s: a stretch of DNA that repeats itself over and over again, CAGCAGCAGCAG… and so on. People carrying too many CAGs in the Huntington’s gene (more than about 35 repeats) develop the disease. In most cases, those affected by Huntington’s inherited a disease-causing allele from a parent. Others may have no family history of the disease, but may have new mutations which cause Huntington’s.

If a mutation ends up inserting extra CAGs into the Huntington’s gene, new Huntington’s alleles may be created. Of course it’s also possible for a mutation to remove CAGs. But research suggests that for Huntington’s, mutation is biased; additions of CAGs are more likely than losses of CAGs.

Selection

As though that weren’t bad enough, Huntington’s belongs to a class of genetic diseases that largely escape natural selection. Huntington’s is often “invisible” to natural selection for a very simple reason: it generally does not affect people until after they’ve reproduced. In this way, the alleles for late-onset Huntington’s may evade natural selection, “sneaking” into the next generation, despite its deleterious effects. Early-onset cases of Huntington’s are rare; these are an exception, and are strongly selected against.

Persistence

These mechanisms of evolution, mutation and selection, can help us understand the persistence of Huntington’s in populations. In general, Huntington’s is rare — 30-70 cases per million people in most Western countries — but it is not entirely eliminated because selection does a relatively poor job of weeding these alleles out, while mutation continues creating new ones.

Dr. Nancy Wexler (shown at right tracking geneologies) has been studying the remarkably high frequency of Huntington’s in Lake Maracaibo since the 1970s. She has found that the high incidence of this disease there is explained by an evolutionary event called the founder effect. About 200 years ago, a single woman who happened to carry the Huntington’s allele bore 10 children — and today, many residents of Lake Maracaibo trace their ancestry (and their disease-causing gene) back to this lineage. A simple fluke of history, high-birth rates, and weak selection are responsible for the genetic burden shouldered by this population.

Dr. Nancy Wexler (shown at right tracking geneologies) has been studying the remarkably high frequency of Huntington’s in Lake Maracaibo since the 1970s. She has found that the high incidence of this disease there is explained by an evolutionary event called the founder effect. About 200 years ago, a single woman who happened to carry the Huntington’s allele bore 10 children — and today, many residents of Lake Maracaibo trace their ancestry (and their disease-causing gene) back to this lineage. A simple fluke of history, high-birth rates, and weak selection are responsible for the genetic burden shouldered by this population.

Solutions?

Currently, physicians don’t have any cures for Huntington’s disease — there’s no miracle pill that will stop the progress of the disease. However, understanding the evolutionary history of the disease — a recurrent mutation that is often “missed” by natural selection — points out a way to reduce the frequency of the disease in the long term: allowing people to make more informed reproductive choices.

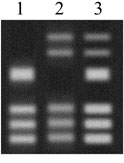

Today, genetic testing can identify people who carry a Huntington’s allele long before the onset of the disease and before they have made their reproductive choices. The genetic test that identifies the Huntington’s allele works sort of like DNA fingerprinting. A DNA sample is copied and cut into pieces. The pieces are then spread out on a gel (see right). The banding pattern can tell researchers whether a person carries an allele that is likely to cause Huntington’s.

Having this information could allow people to make more-informed reproductive decisions. For example, at Lake Maracaibo, researchers and health workers have tried to make contraception available to the local population so that they can make reproductive choices based on their own family history with the disease. But whatever people eventually decide to do with this knowledge, a deep understanding of the disease would not be possible without the historical perspective offered by evolution.