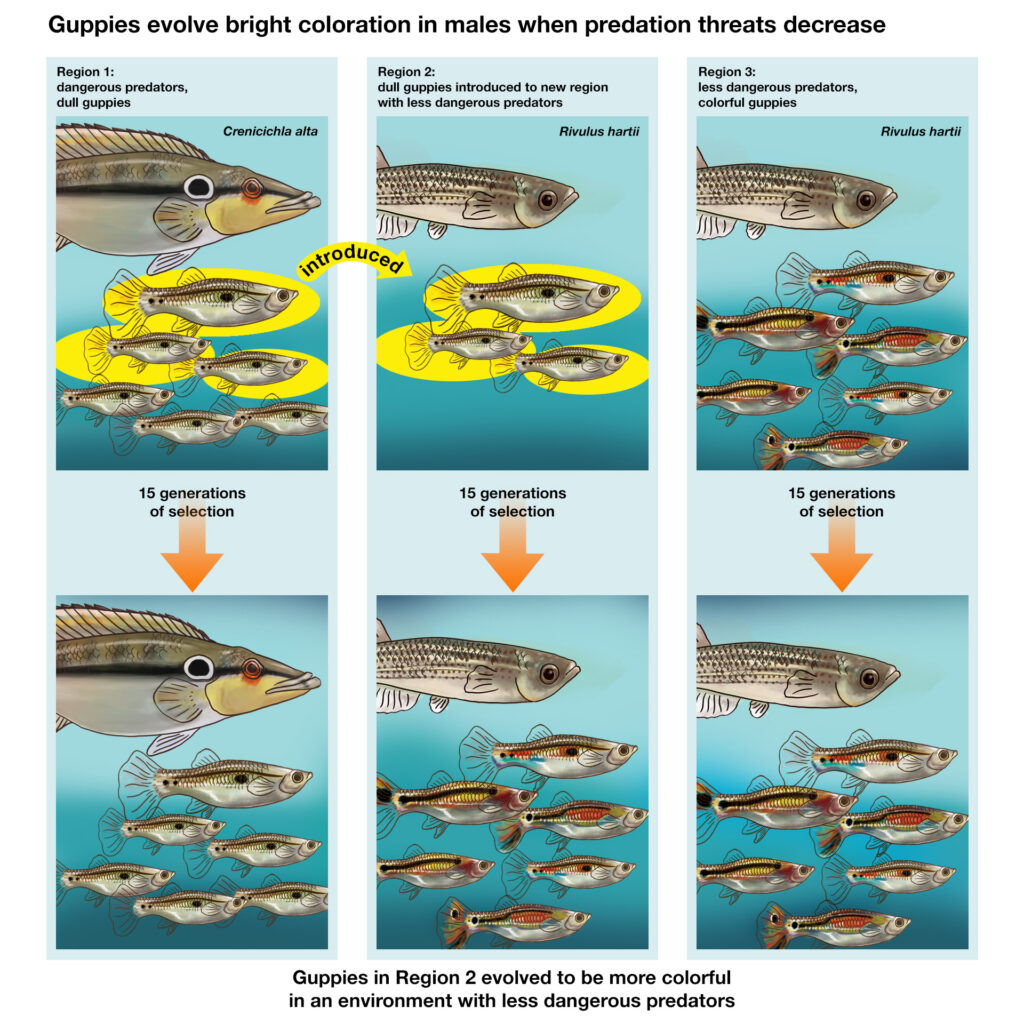

Experiments also show that populations can evolve. For example, biologist John Endler conducted experiments with the guppies of Trinidad that clearly show selection at work. Female guppies prefer colorful males as mates. However, colorful males are also more likely to be eaten by predators because they are easier to spot. Some parts of the streams where the guppies live have less dangerous predators than others, and in these locations the males are more colorful. In locations where there are more dangerous predators, males tend to be less colorful. Of course, the likely explanation for this observation is that the guppy population in each area has evolved in response to the competing preferences of females and predators present in that particular environment. But Endler did not stop with that observation. He also performed an experiment on populations in the wild.

He transferred guppies from an area with dangerous predatory fish (that is, he took guppies from a group with dull-colored males) to a region with less dangerous predators and left them for about two years (~15 guppy generations). Then he came back to see if they had evolved. In this region, without hungry predators picking off bright fish, sexual selection favored males that stood out. The population had rapidly evolved into one with brightly colored males. This demonstrates that genetic variation within a population provides the raw material for rapid evolution when environmental conditions change.

There are many other cases in which experiments demonstrate how evolution can occur. These include:

Reviewed and updated, June 2020

Experiment is described in Endler, J. A. (1980). Natural selection on color patterns in Poecilia reticulata. Evolution 34: 76-91.