As with any exhibit, displays incorporating trees benefit from a collaborative design approach. When possible, try to include the following individuals in the discussion:

- Educators

- Exhibits designers/developers

- Graphic designers

- Evolutionary biologists/scientists

- Audience (i.e., through front end and formative research and evaluation: soliciting feedback from visitors, talking to docents, volunteers, and guest services, etc.)

To learn about collaboratively designing tree displays, check out these case studies:

- Explore Oregon! Evolutionary trees in a local natural history museum

- Evolving Planet: Communicating the entire Tree of Life

Graphic design specifics

All trees are not created equal. Research suggests that even subtle differences in the graphic design of your tree can make a big difference in how well people understand it. To optimize your trees, you’ll first need to familiarize yourself with some common pitfalls in interpreting trees:

- Find out about common tree misconceptions.

When you put pen to paper, keep in mind these basic design principles that are supported by research on tree reading:

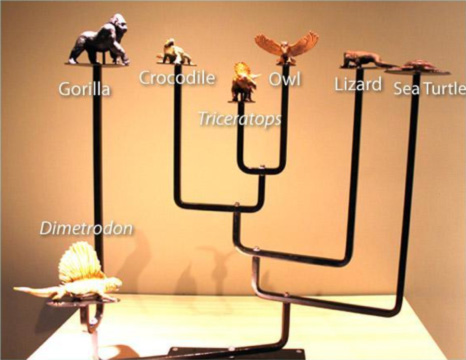

- Use a tree with square corners. It might be tempting to draw a tree that resembles an actual tree with leaves and branches; however, this tree design is difficult to read and interpret, encourages misconceptions about evolutionary processes, and often cannot reflect the scientific understanding of evolutionary relationships.

- Keep it as simple as possible. Minimize layers of complexity. Consider the main story you want to tell, and try not to show too much more.

- Include a timescale or arrow of time. This doesn’t have to be calibrated. Even a simple arrow showing the direction of time can help. It is important to include time on the tree, but unless it supports your main message, don’t overwhelm visitors with lots of additional information about the timings of different events. It’s important to consider what you want visitors to take away and what the context of the exhibit is (e.g., if there are other references to time or timelines in the exhibit).

- If you are including humans or another taxon that is widely perceived to be “advanced” on your tree, rotate branches so that this taxon appears in the middle of the tree, not at one side. This will help discourage the erroneous impression of evolutionary progress.

For more important tips on how to graphically design your tree (including before-and-after examples), consult the following resource:

Interactive displays

Most trees in exhibits are static graphics, although some institutions have used other formats such as 3-D designs with rotatable branches or computer interfaces (e.g., animated videos and games). Research about the use of dynamic visualizations and 3-D representations in teaching about trees is still in its early stages. If you want to incorporate this sort of visitor interaction with trees into your exhibit, research does suggest that providing opportunities for visitors to actively engage with or control an interactive (e.g., pause or replay a video) helps support learning.

For examples of multimedia/interactive presentations about the tree of life, see:

Language and interpretive text

Because trees are not intuitive, you will need to help the public understand your trees with interpretive text. There are few standardized guidelines for this text, but we do know that visitors often go to captions first, so be sure to explain what your trees are meant to show in a caption with clear, familiar language — such as:

- “Evolutionary relationships among hummingbirds.”

- “Hummingbird family tree.”

- “This tree shows the relationships among some common hummingbird species.”

Also keep in mind that the phrase “common ancestor” is often misunderstood. Use “shared ancestor” or “ancestor in common” instead.

Once the tree itself is designed, it’s time to consider its broader context…