In 2014, Camillia Matuk, Assistant Professor of Educational Communication and Technology at NYU, interviewed Elizabeth White, an exhibitions designer at the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History, about their new exhibit on the natural history of Oregon. Explore excerpts from that interview to find out how research on perceptions of evolutionary trees and formative assessments shaped the trees in that exhibit.

- Exhibit summary

- Choosing the trees

- Designing the trees

- Supporting visitor understanding

- Addressing new research

- Recommendations

Exhibit summary

The institution: University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History, Eugene, Oregon, annual visitorship of 15,000-18,000.

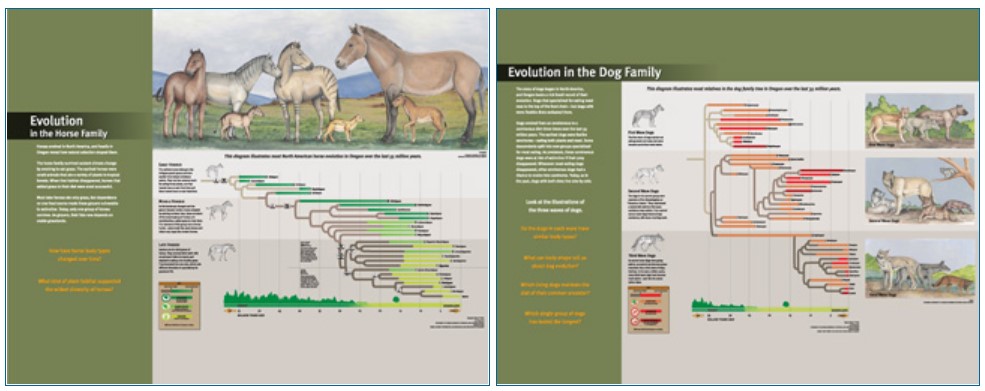

The exhibit: The 2700-square-foot, semi-permanent Explore Oregon! exhibit opened in May 2014 and showcases the natural history of Oregon. A small but important component of the exhibit involves trees showing the evolution of dogs and horses. In addition to relationships, the trees depict diet and character changes within these families, coevolution, past diversity of species, and when different lineages went extinct. Each tree is part of a 70-by-54 inch graphic panel and is associated with a display case of fossil material. The trees are situated within a larger section devoted to evolution that includes an introduction to natural selection, shared traits, common ancestry, and phylogenetics.

Goals for the trees:

- To communicate that fossils found in Oregon are relevant to research on interesting evolutionary questions

- To communicate the relationships among modern/ancient dogs and horses

- To communicate levels of species diversity at various points in time

- To visually depict the process of adaptation over time

- To reinforce the idea that evolution is not progressive

Who worked on the exhibit: A large staff, including project managers, science advisors, exhibit designers, educators, and evaluation personnel, as well as an outside design firm.

Choosing the trees

Horses and dogs have an excellent fossil record in Oregon and evolved in North America. We have a lot of these fossils in our collections, and we wanted to make sure that we had physical evidence to support what we are talking about. Graphic charts and illustrations are great, but people who go to museums want to see stuff. Also, a lot of people have dogs, and a lot of people in Oregon have horses too. We thought we would start with animals they are familiar with to introduce topics they might not be familiar with, evolution and phylogenetics.

There were some discussions among the science advisors about which taxa to include and which are valid genera. But ultimately, they came to ready agreement. We also edited down the horse tree to include just North American genera.

The trees and the relationships themselves, we took from the published literature. There was some healthy debate among the science advisors over the validity of certain parts of the trees, but they worked it out. We have a doctoral candidate in paleontology whose specialty is horses, so he was easy to consult. And one of our advisors had done a lot of work with canids. So we had lots of local resources to pull from.

Designing the trees

Before we started to really focus on designs, we read Teresa MacDonald’s article about tree design and several other articles about interpreting evolutionary diagrams. One of the key points there was connecting the tree with exhibit content, which we did with our fossils. Other key elements of tree design that were driven by the literature on communicating phylogeny were that the tree should be oriented left to right, that branches should be bracket shaped, to feature a group that includes lots of extinct species, and to feature character state information. An explanation of time was also something we wanted to include. One article mentioned careful placement of the human taxon, but we didn’t have to worry about that since we were dealing with dogs and horses.

We also looked at the website from a conference about trees in museums. I went through the database of museum tree photos to identify visual elements that we thought we should use for our pieces. A lot of the references that are collected on that site show wavy and stylized branches, but we wanted to be direct and specific. In a temporary exhibit, we’d had a tree that did a good job of showing when things lived and died, but the connections weren’t very specific. We wanted these new trees to be really up-to-date and exact. But we also wanted to present them in ways that were engaging, colorful, and visually appealing at first glance. We wanted to make sure that they weren’t like the charts you often see in publications—just black with silhouettes. We thought it was a good idea to include reconstructions because everybody wants to see pictures of the animals we are talking about.

We designed the trees with a horizontal branching format to make sure that the accuracy was there. You can see exactly how long each lineage lived, how they overlapped, and when they went extinct. We also went with the horizontal aspect because of space constraints — only a horizontally oriented tree would let us use a visually impressive scale and allow visitors to read the names of the genera — and because we wanted it to flow along with how people generally read time, from left to right.

Initially, we talked about doing 3-D trees, but it didn’t work out with the space and cost. AMNH has 3-D trees where there are specimens at the ends of the branches. And there was a phylogeny of horses at the John Day Fossil Beds that had more abstract wavy branches and that was made of metal and bumped out from the wall, more like an art piece. But it just wasn’t feasible for us, and we were concerned about readability.

We got lots of feedback on our initial designs from staff and from personnel at our graphic design firm who didn’t have a science background. When we started, we included much more information — silhouettes, graphics that indicated character changes — but it got so complicated that people didn’t know where to start. We just had to figure out what we really wanted to focus on and what we could easily represent.

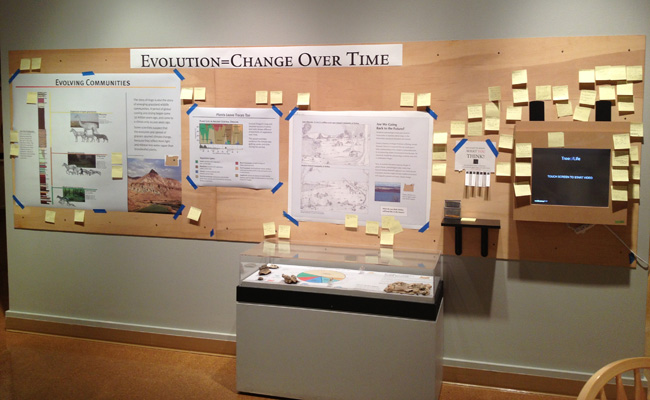

We also had grant and donation funds to do paper prototyping for our exhibit and get reviews and feedback from the public before final design and production. We gave people post-it notes to write on and stick up, and we ran focus groups and surveys. Through that, we found that extinction was an important component in how people relate to the trees. When they see a fossil record depicted as a phylogeny, they always want to know why the animal doesn’t exist any more. The findings also confirmed visitors’ preference for large tree graphics over written descriptions of evolutionary history. They also wanted to see large graphics of the animals. And we simplified some things. We tried some trees that were really busy and crowded with symbols. People reviewing it would see it, and not know at all what was going on.

Supporting visitor understanding

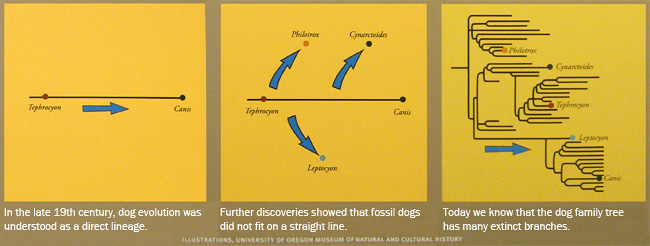

We have an area in the exhibit that gives an introduction to what trees are. It includes a six-minute David Attenborough video called the Tree of Life, a diagram that shows how people misinterpret evolutionary trees as being literal family trees like genealogies, and a section that talks about the inheritance of shared characteristics. We also have a section relating to a particular canid fossil we have that describes how the scientists who discovered the skull, at the time, thought of phylogenies as a ladder. We use this example to discuss historical change in how relatedness is perceived. We have diagrams that show how the tree originally looked, with one form morphing into another, versus what we see today, with common ancestors connecting related organisms. So we directly discuss the evolution of the visual representation of trees.

I’ve noticed that a lot of institutions use sidebars to highlight the animals, but we wanted the tree to be the centerpiece and all of the extra information to relate to what’s happening in the tree. When they first walk up to this section, visitors will probably see the tree right after the objects. And instead of just having them look at the tree and get meaning out of it on their own, we have questions associated with the tree that encourage them to trace patterns of ancestry on their own and really think about these changes in diet.

Addressing new research

No exhibit should ever really be permanent because of changes in scientific research. Probably in a year, the content in our trees from the published literature will be rewritten because of additional fossil finds or additional DNA research. We expect this exhibit to have a 10-year life span, but each section of the exhibit also has an area for updates, so that we can keep current with new research. Also, an advantage of our rail system for installing graphic panels is that it allows us to remove one panel and replace it, while leaving the rest of the exhibit intact.

Recommendations

What was effective: The exhibit isn’t open yet, but we do have plans to work with a science education and evaluation group on campus to evaluate the exhibit as a whole and particularly the section on evolution. I really think that having relatable and familiar animals is helpful for conveying the message about evolution. Also I expect the graphics to be a big hit with everyone. Once we’d finished the paintings of the animals as they would have looked, people had a really immediate response to them. Having a regional tie to Oregon should also be helpful because a lot of times people who are looking at the tree and the fossils enjoy already knowing things that we mention — like where John Day Fossil Beds are.

If they could do it again: Next time, I would like to make the graphics bigger. I was really impressed with the ones at AMNH that were so large. I think it would have an impact. Also, there’s only one other natural history museum in Oregon, so there weren’t a lot of local people to collaborate with or talk with. I did a lot of Internet research, but I wish I’d been able to talk to more people directly.

Advice for other institutions: Look for an association between the region or the institution and the tree to provide a clear reason that the tree is there. Associated fossils and biological specimens will help people get interested in the tree. Also prototyping and letting lots of people see the ideas for the exhibit in the design phase was ridiculously helpful! And talk to other people; other designers of exhibits and museum professionals have good ideas and experience with what works.